September 1 – September 4, 2021

May 9, 2012 - September 7, 2021

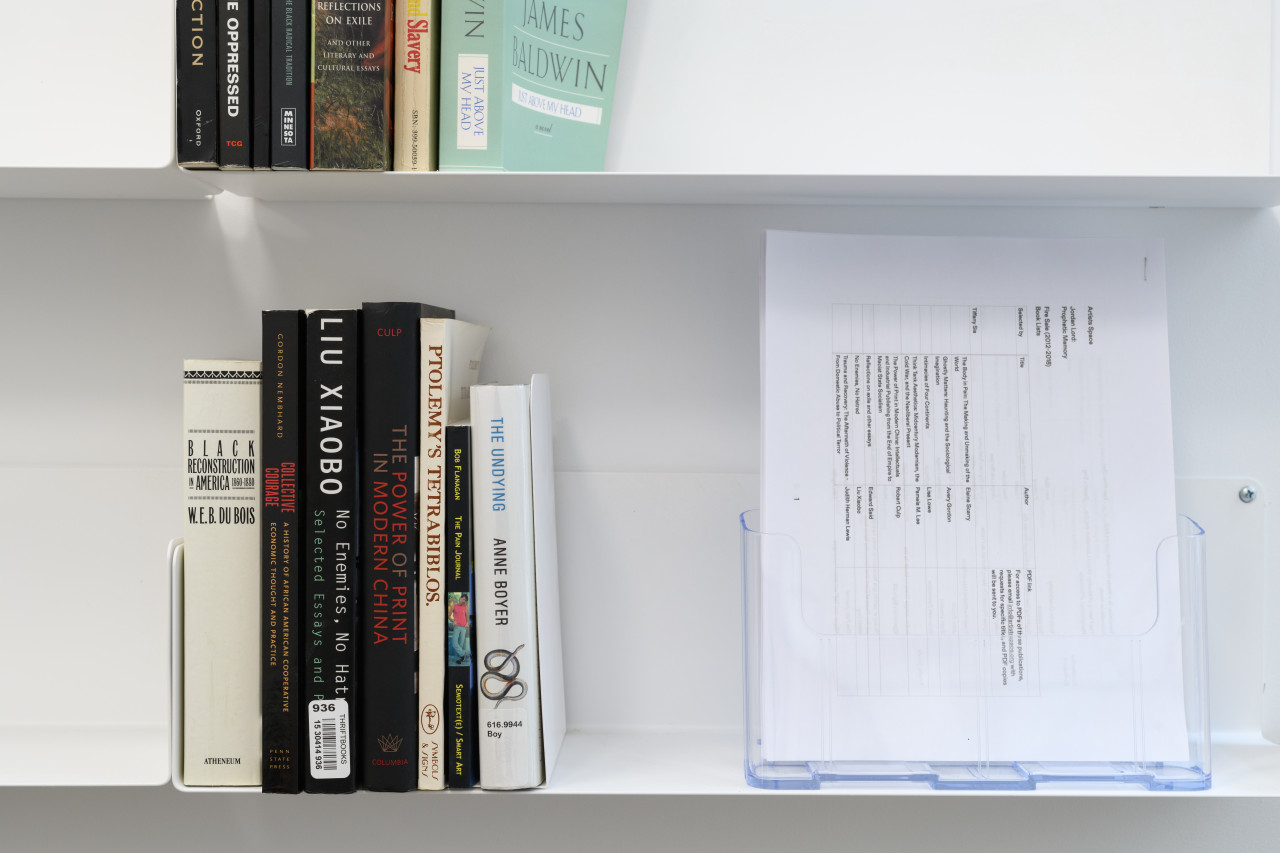

Artists Space is pleased to present Prophetic Memory, the first institutional exhibition by Jordan Lord, which will take the form of an unfolding series of interventions, events, and presentations across a multiplicity of sites. An artist, filmmaker, and writer, Jordan Lord’s work concerns the conditions of disability and access, and legacies of debt and neglect under capitalism. Conceptualized amidst the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, their project began with a response to the ways in which sharing physical space entails forms of segregation and deferred risk for disabled audiences, among others. Elaborating the means by which an exhibition might be accessed both spatially and temporally, Lord’s exhibition centers on questions of liveness, including the means by which Artists Space represents and records the “liveness” of an exhibition.

Drawing on Lord’s nearly decade-long engagement with Artists Space (as an intern, bookstore manager, reading group member, events programmer, and artist), an ongoing series of updates to the Artists Space website will accompany a series of carefully organized online screenings and public programs this summer. The exhibition is designed in collaboration with Lord’s grandmother, an interior designer, and will culminate in a film on which they have collaborated this fall. Through its many facets, Lord's project explores issues of memory, value, access, architecture and design, and institutional engagement from myriad vantages.

Content note: Discussion of white supremacist ideology/violence/policy and ableism/ageism

I can’t sleep without watching TV; things I’ve seen before work best. I don’t usually remember what happens. It helps not having to remember, the feeling that whatever’s happening onscreen will be there again the next night or the next time I need to rewatch it to fall asleep. It’s the same with the parts that made me laugh or cry; in order for them to work again, I have to forget enough to be surprised when the same thing happens.

My grandmother sleeps with the television on, too––almost always the news. Fox News plays on her TV, even when she’s not in the room. The sound is often so low I’m not sure she can hear it, though I wonder if she notices the headlines, as she falls in and out of sleep. As much as they provide summary and selectively caption parts of what’s said in order to instruct the audience in what they’re meant to take away, the headlines also serve as mnemonic devices.

The TV makes it hard to concentrate when I go into her room to visit. Whether day or night, most commercials seem to market to elderly and disabled audiences, touting new pharmaceuticals, cures for pain, memory-enhancing drugs, mobility aids. It’s not just that Fox News directly caters to the conservatism of many elderly white people. Cable news in general seems to count on the fact that many elderly and disabled people spend a lot of time at home or in medical facilities––in either instance near a TV1 . Many of these audiences experience prolonged periods of isolation, which perhaps feel less isolated with the presence of people’s faces onscreen and voices in the background.

Last week, I went over to my great aunt’s house with my grandmother. She told stories about her life to her sister and her sister’s boyfriend, ones they’ve heard many times before; my great aunt also lived through many of them. As they spoke, they jumped from these stories to fears about what will happen in the future, based on what Fox News has said about the present. All three of them agreed that the world is ending, and they are glad they are old enough that they won’t be here when the end finally comes.

--

In February, artist, filmmaker, and writer Tiffany Sia presented a show at Artists Space––actually, at the same time I was initially invited to present my show alongside hers and Adjua Gargi Nzinga Greaves’, though I didn’t have enough time to be ready to make a new project at that time and am still not sure that I do.

Tiffany and I met through Instagram in May, and as we messaged each other, it felt to me as if we had met before.

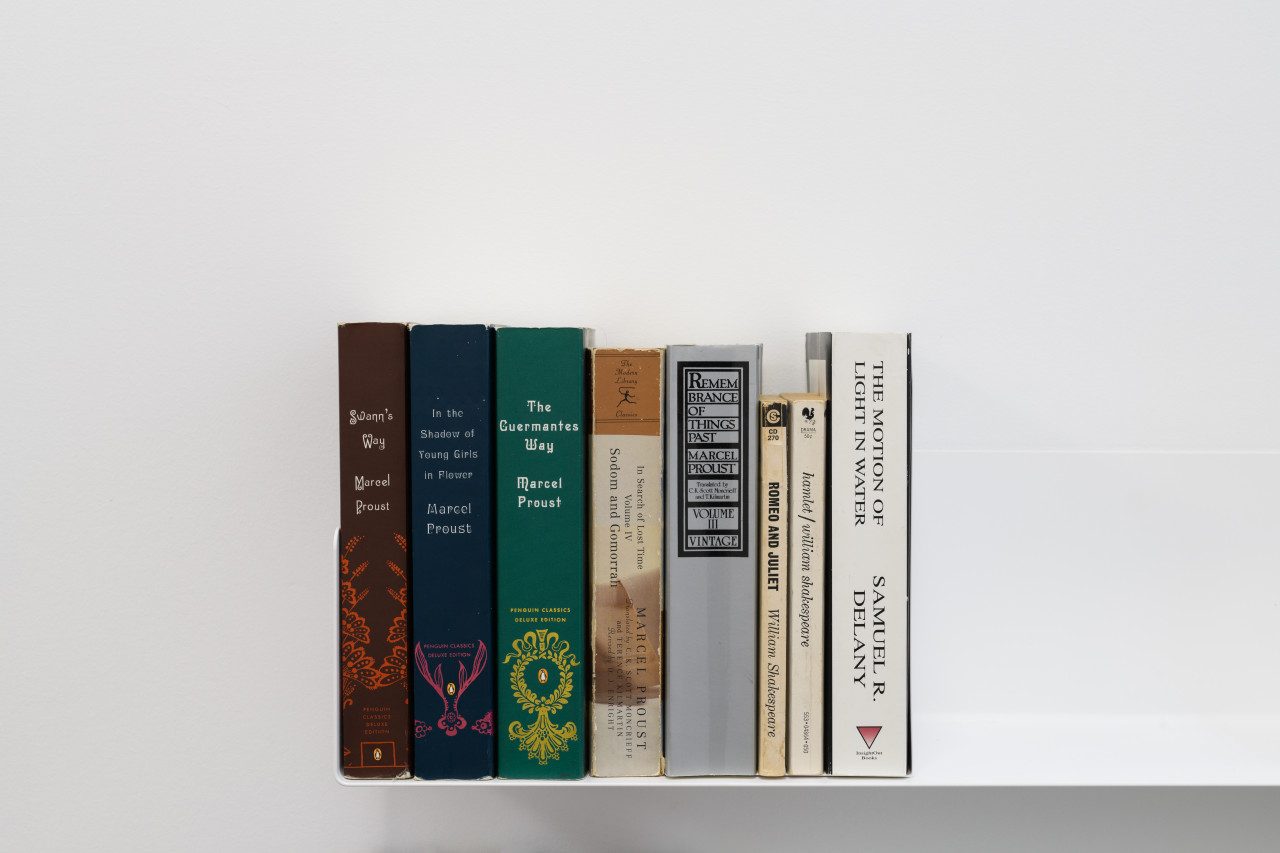

I only just finished reading her amazing book, Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕, which was included in the Artists Space show as a printed book with a shiny foil exterior; a long printout laid across a table; and on a website designed for the show as a seemingly infinite scroll that you had to zoom into in order to make legible. I lost my spot every time I closed that tab on my browser and had to scroll to find my place again.

The text concerns many things including the confrontation between Tiffany’s memories of living through the struggle against police repression in Hong Kong in 2019; how much of her experience was mediated between being there, trying to record it, watching livestreams of the events––or “bodies recording history”; and the events misinterpreted often mistranslated on the news at home and abroad, the traumas of remembering it, still living it; and the colonial history of Hong Kong that is still playing out in her family, in her life, and in the world.

I wrote down so many lines that I needed to remember. In many senses, each one might be used to punctuate each section of this text.

But for now, I’ll start with this one:

“It is exactly with the authority of the future, the authority of the victor to decide how school textbooks will enumerate these events, and yet still, how does one write about the process of living through a metastasizing present, a becoming of history that is yet unfinished? What will disappear from the record? What stories did not even make the news?”

--

In a day’s cable news cycle, the same footage is reused and the same stories are retold by different tellers, creating an unspoken consensus about what is happening, what is live. A considerable amount of airtime is devoted to framing old things as new things without a past, while either choosing not to report on things that are still happening or actively insisting that they are over and done.

The other day I watched one of Fox News’s most popular opinion shows, The Ingraham Angle, deploy the all-caps red-lettering suggestive of both emergency management systems and live breaking news to issue an “Angle Alert” with the following headline: “Liberal Activists Poisoning Our Education System.” The show’s host, Laura Ingraham, spent the hour-long episode bringing on 5 different guests to speak about many different things but always connected them back to the same message: Fox News has declared a state of emergency over the teaching of Critical Race Theory in public schools and institutions.

In the September 2020 lead-up to the presidential election, while avoiding responsibility for hundreds of thousands of people who had died from Covid-19, Donald Trump issued Executive Order 13950, which banned federal agencies and federal funding from educating employees about or formally recognizing the existence of systemic racism and sexism. This order was co-drafted by and was conceived in response to watching right-wing activist Christopher Rufo’s appearance on Tucker Carlson Tonight, in which he took aim at the use of what he described as the ‘pervasive’ spread of Critical Race Theory in Diversity, Equity, Inclusion trainings funded by the federal government.

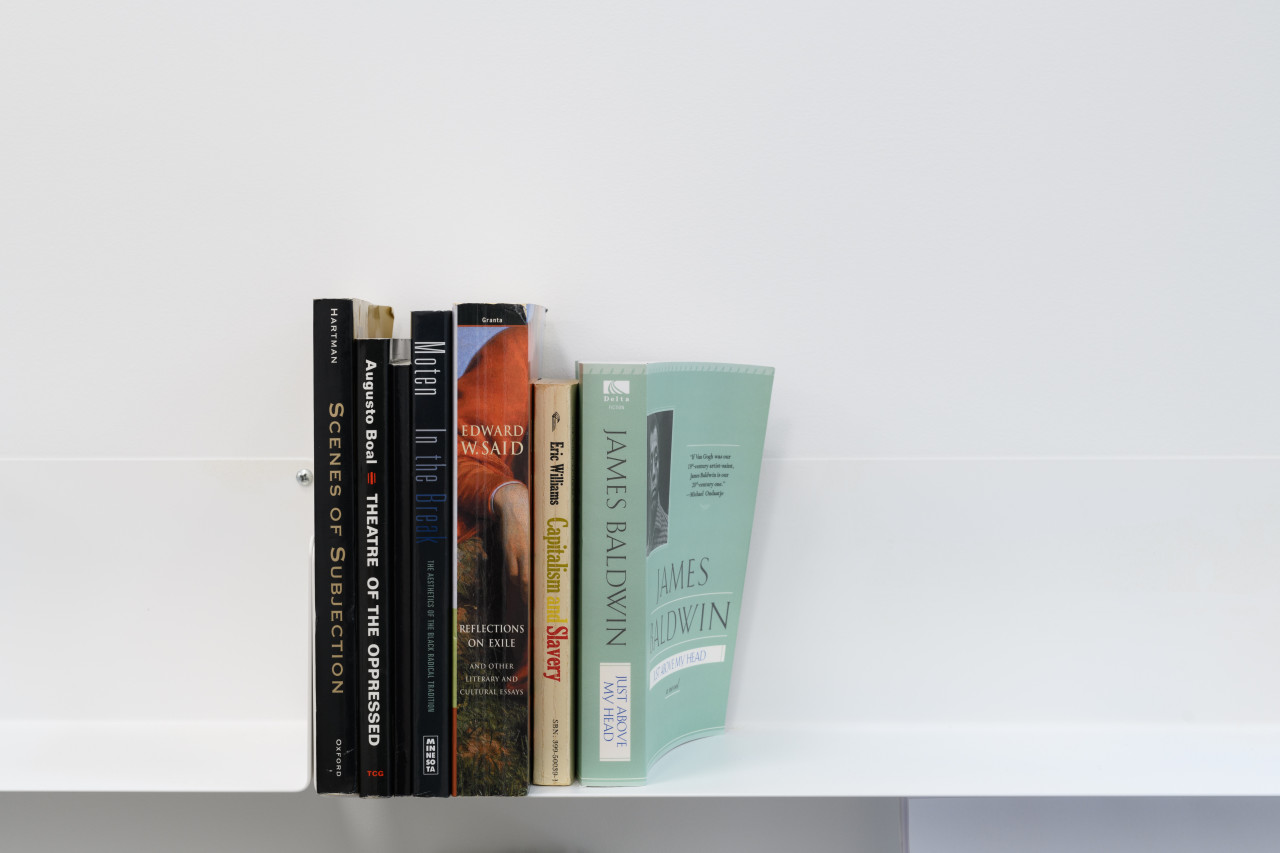

Rufo, Fox commentators, and Republican politicians use Critical Race Theory (CRT) as a catch-all term for teaching that Black and Brown Americans continue to experience forms of structural violence and oppression. In doing so, they seek to combat the study of the inseparability of American politics, law, and history from the racism/anti-Blackness of American institutions.

The recent explosion of state policy and white right-wing panic about CRT in public education has been voraciously commented on and simultaneously engendered by its coverage on Fox News. Not incidentally, much of Trump’s, Rufo’s, and Fox’s commentary emphasizes the so-called “virulence” of CRT, alternately framing it as a “sickness” or an incendiary threat to infrastructure, what Laura Ingraham calls “racial arson.”

Much like Rufo casts Critical Race Theory as “the perfect villain,” Fox News pundits present CRT as a more dangerous and looming threat than the actually existing ongoing viral pandemic, reanimating the white panic that fomented around the spectacular imagery of burning police property during the 2020 uprisings against the police.

These are fears and strategies as old as those that created the Second Amendment, white militias, fugitive slave laws, Jim Crow, and police forces, all of which were devised to enforce a regime of racial terror and to ensure white supremacy by legally and physically rooting out Black resistance and self-defense2. The white legal battle to suppress the teaching of CRT is itself not new; in 2010 Arizona passed a state law banning the teaching of CRT in the classroom before being overturned by the courts.

Legal scholars like Kimberlé Crenshaw, Derrick Bell, Neil Gotanda, and Cheryl I. Harris developed CRT as an academic discipline in the late 1980s and early 1990s, elaborating historical and critical interpretations of legal concepts like colorblindness, whiteness as property, and retrenchment of discrimination law as a viable means of redress for Black Americans. In their work, these scholars predicted the very strategies Republicans are currently deploying to create policies aimed against CRT in education. These legal efforts hinge on interpreting discrimination law through a doctrine of colorblindness that enables them to present white people as victims of discrimination, as a means of protecting the property interest vested in whiteness.

Though Executive Order 13950 has been rescinded, in the 10 months since Rufo’s initial Fox News appearance, 27 states have proposed copycat legislation aimed at preventing Critical Race Theory from being taught in public schools, under the guise of anti-discrimination legislation or promotion of “patriotic” education or prohibition of teachers taking political stances on “controversial issues.” Though the stated aims of the bills vary, there are fundamental underlying similarities, and Rufo himself advised the language of many of them. As in EO13950, these bills seek to eliminate learning environments, in which whites might feel “guilt,” “discomfort” or “responsibility” for “actions committed in the past.”.

Kimberlé Crenshaw makes quite clear what is at stake in CRT and the relationship it draws between the past and present, as if the inverse of that which Fox News and the anti-CRT legislation seeks to impose with their state of emergency: “[CRT]’s an approach to grappling with a history of white supremacy that rejects the belief that what's in the past is in the past and that the laws and systems that grow from that past are detached from it.”

--

My grandmother says if she could live at any time in history, she would go back to her childhood, when her large family all lived together, when her parents took good care of her and her siblings, and they felt safe.

She remembers her mother, who lived with her. After she had a stroke, she took care of her mother with her daughter Angelique, who was a child at the time.

She remembers that when she was having a problem, she would call her mother just to hear her voice. She wouldn’t tell her what was wrong, though her mother always knew when she wasn’t alright.

She says she can still hear her voice. To remember it, she says it out loud.

She says all she needed to feel everything was okay was to hear her pick up the phone. She would call her, and her mother would answer, and she would say, “Hell-o?”

--

Forgetting is so much of what animates the very act of remembering. Or, perhaps more specifically, forgetting is what makes the act of remembering become live again.

--

Since I travelled to be with my family in MIssissippi this summer, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told that “the pandemic is over” and that “we’re moving on with our lives.”

--

In February, my sister and her family were fortunate to take shelter in a waterless, occasionally powerless hotel room, from the Texas winter storm that caused power outages and water shortages that killed between 150 and 700 people. It’s hard not to imagine future energy crises and more subsequent deaths in Texas this summer, knowing that the root causes of the power failure still have not been remedied.

On June 16th, ERCOT, the power company responsible for the majority of Texas’s electricity, asked its customers not to set their thermostats below 78 degrees before summer had even begun. Though I’ve not been able to access complete demographic data on who died in the winter storm, one of the primary sources of undercounting deaths from the storm––much like the undercounting of deaths from Covid-19––has been from not counting deaths of elderly and/or disabled people, who died due to a lack of access to medical equipment or care caused by the catastrophe: people who had medical conditions such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and heart disease––all conditions for which you see commercials for treatment options on Fox and other cable news stations.

Meanwhile, the reporting on anti-CRT laws has surged exponentially from Fox News to all other major media outlets.

In the short time since all this has occurred, I received a text message from ConEd encouraging NYC residents to minimize their A/C usage, though I was in Mississippi.

As of July 3rd, 719 people had died “sudden and unexpected deaths” in British Columbia, at least 95 people had died in Oregon, and at least 30 died in Washington, because of the historic heatwave that caused temperatures to surge far over 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Comparing the number of so-called “excess deaths” with the average expected number of deaths over a given period of time allows estimations of how many people die from an “unexpected” catastrophe. However, the repetition of other instances of the same circumstances, as well as their prognostication by climate modelling or other means of intuiting what’s to come, throws into relief what’s at stake in claiming such an event or the deaths that result from them are “unexpected.”

--

When something that’s still unfolding stops being news, it can become new again, more often than not as an emergency.

--

The Fox News model for tapping its audience’s memories evokes a state of emergency parallel to the life-and-death stakes of the emergency room. Far from trying to suggest that racism is an illness, I am thinking about those in its audience, who are actually chronically ill and spend a good deal of time in emergency rooms or hospitals.

Though it’s so widespread as to be, perhaps, the dominant way of understanding life in a cascading series of crises, living in a constant state of emergency creates a kind of contradiction in terms.

Constancy implies something that cannot be fixed because it will continue indefinitely, but the emergency presumes the necessity of arriving unexpectedly and either fixing it or it coming to an end. This is the difficulty of trying to live through chronic time in a state of emergency––either chronic illness, which needs immediate and constant attention but cannot be cured, or a chronic condition across history, a past that won’t stay past.

As Johanna Hedva writes, chronic illness renders emergency itself paradoxically predictable, “a life lived with the certainty that one’s fragile body is the only certainty [...] though it feels like the emergency has been paused, I know it will return.”

This certainty of return also makes me think about the ways we’re always in the process of making history as history is simultaneously making us. Whether this can be reduced to a pattern of repetition is at the core of what I’m trying to ask here, knowing that the act of remembering the past can also be made up of simultaneously forgetting it in ways that make it come back to life again.

This live element of the past both generates states of emergency as well as the urgency of reckoning with the past and how it is reanimated in the present. Or perhaps to follow Johanna’s lead, beyond even urgency, it underlines the certainty that it will return and must be reckoned with.

--

Which past and how it comes to life again fundamentally depends on who is there to take part in the process of repeating, forgetting, remembering, (re-)living it.

--

Something I’ve been feeling with a great deal of anxiety is that my grandmother has put her trust in me to make a film about her life, in which she tells her memories, while knowing that we live in two diametrically opposed understandings of the past and present.

Tiffany’s book helped me understand this in terms of “a compression of timelines.” She describes the “unbearable” conflict of witnessing news reports compress the brutal emergencies of one present with the apparent calm of another. Tiffany later quotes Jasbir Puar who reminds us that certain forms of restfulness can only come about through decisive forms of forgetting.

I’ve told my grandmother that the film is a way of remembering her. But the emergencies imposed on these acts of memory make me fear that she will experience the film as a betrayal of her trust.

I was just re-reading Johanna’s “Letter to a Young Doctor,” in which they try to articulate what it is like to live with chronic illness while being entangled with a medical system that only seeks cure. I was struck by their discussion of the meaning of trust in the doctor-patient relationship and that, in some sense, it also seems like a definition of liveness or living at the same time:

Johanna writes, “Another therapist recently told me, ‘Trust is that you are here.’ I thought of flesh, decaying, painful, remembering, that is bound to being here. Lingering, bearing. [...] Of my many pieces that are all somehow here, lingering, remembering, and of some ways we might start putting things together, again, or for the first time, or letting them stay in pieces, just honoring that they are here, that you are here, and so am I.”

--

While I’m staying with my family on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, I drive to the beach every morning to be able to think or to clear my mind. I park near a jetty that ends in a pier that was broken by a storm. The planks that once connected it to the jetty are missing, leaving it stranded in the water.

To test out my new wireless microphone, I asked my mom if she would let me film her walking and talking––a familiar documentary trope, which is often used to animate narratives that might otherwise feel static––along the jetty. When we reached the end, I asked her if she would tell me what she was thinking about as I filmed her.

She said, “When you see the brokenness of the bridge, you think of all the people that have walked that bridge. And their lives have been broken, and you wonder, have they been able to mend things? With the pieces, I think of, you know, when we create things in our lives and we're sorry for things. You know, the Word says that when we ask for forgiveness, He casts it into the sea of forgetfulness to never be remembered again. Ever.

It goes out there with the tide and never comes back. And all those broken dreams...that feel shattered. There's new life again. I see hope. See, hope. I see hope. I just, I see it in the end, the waves. I see it in the sea...as it goes out and comes back. Because it's just washing it. Washing it clean.

Huh.

And it's okay because, you know, I mean, He never remembers that. The only reason that it ever comes back is because it's our memories that bring it back. He forgets it. He wipes the slate clean, it's a clean slate. They disappear. I'm talking about when we ask for forgiveness for things that we've done that...He literally wipes the slate clean...never to be again.

And only we bring them back.”

Footnotes

1. See Carolyn Lazard’s artwork Extended Stay, 2019.↩

2. See also the text of Cameron Rowland’s exhibition "Deputies", (2021).↩

Sources

Extended Stay

Too Salty Too Wet 更咸更濕

printed book

long printout

seemingly infinite scroll

Angle Alert

Executive Order 13950

co-drafted

Christopher Rufo’s appearance on Tucker Carlson Tonight

coverage on Fox News

virulence

sickness

racial arson

the perfect villain

the Second Amendment, white militias, fugitive slave laws, Jim Crow, and police forces

"Deputies"

in 2010 Arizona passed a state law banning the teaching of CRT

colorblindness

whiteness as property

retrenchment

27 states

“guilt,” “discomfort” or “responsibility” for “actions committed in the past"

Kimberlé Crenshaw makes quite clear

between 150 and 700 people

before summer had even begun

a lack of access to medical equipment or care

ConEd encouraging NYC residents to minimize their A/C usage

sudden and unexpected deaths

chronic illness renders emergency itself paradoxically predictable

decisive forms of forgetting

"Letter to a Young Doctor"

![Head on view of a projected video. The screen shows three figures sitting and includes closed captioning that reads "[Mimi laughing] Bet you don](https://artistsspace.org/media/pages/exhibitions/jordan-lord/3249739822-1631238832/prophetic-memory-11-1280x.jpg)