This has become mine, this unholding. Whereas, with or without the setup, I can see the dish being served. Whereas let us bow our heads in prayer now, just enough to eat;

– Layli Long Soldier, WHEREAS (Graywolf Press, 2017)

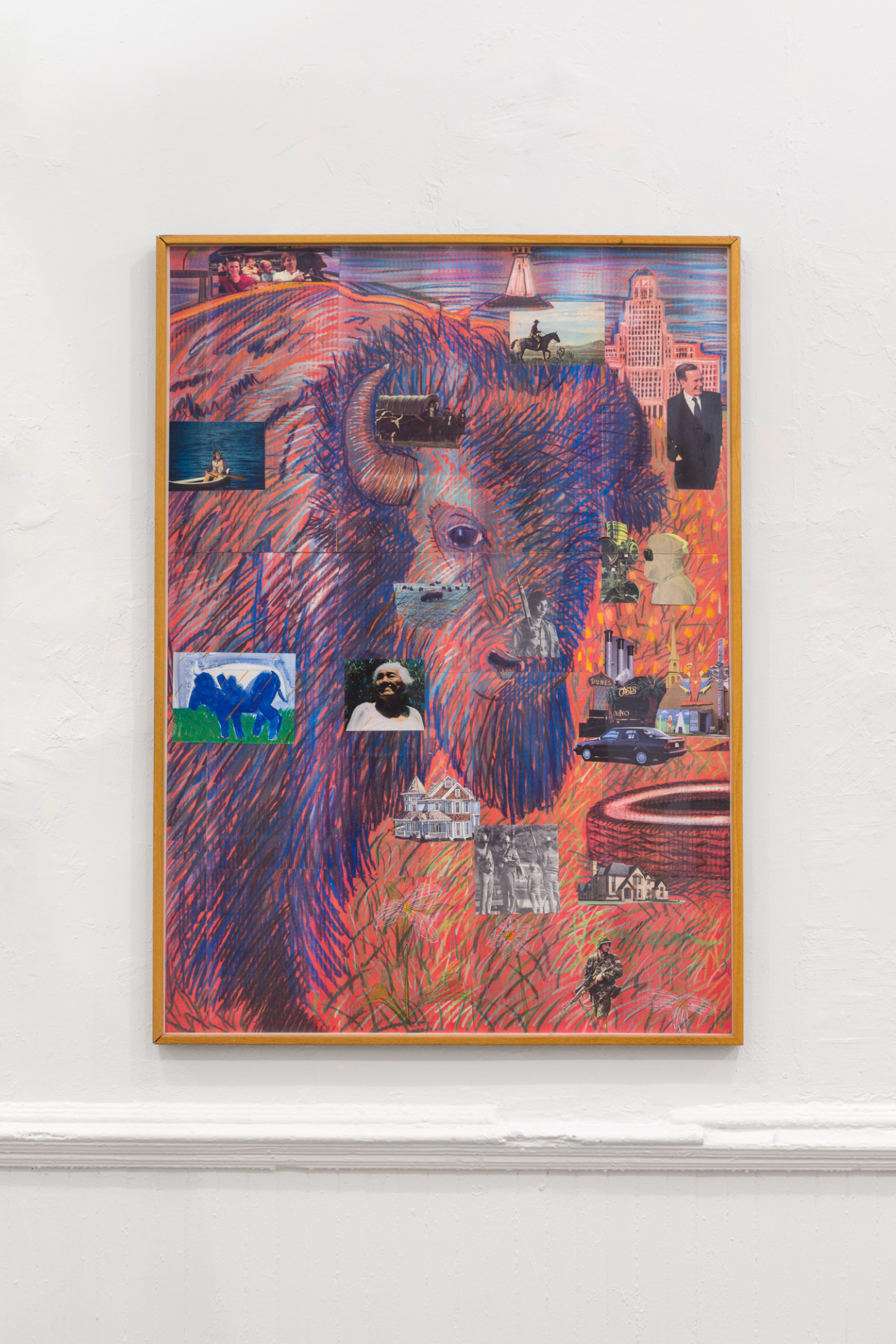

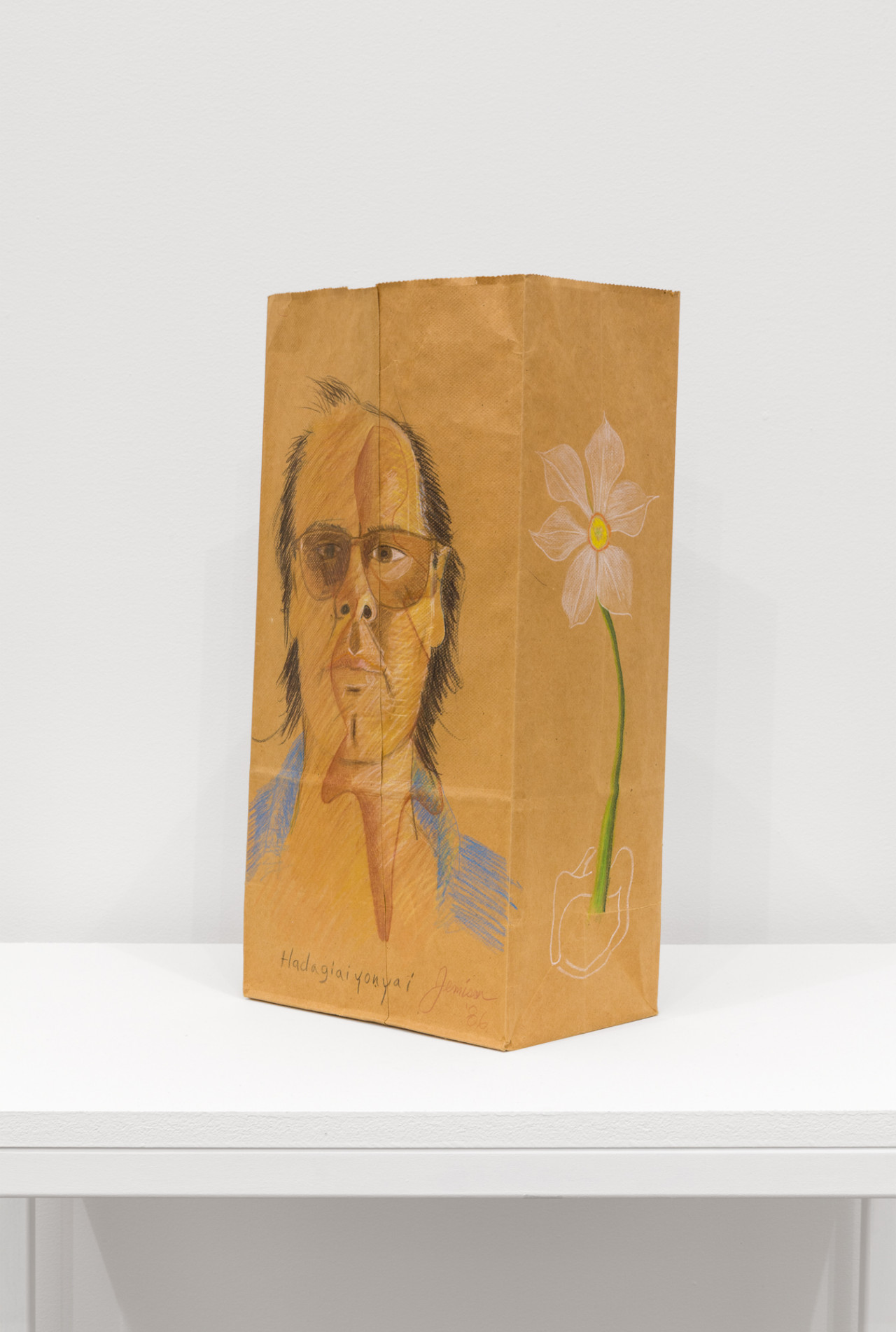

Artists of Indigenous heritage have, for many decades in New York City, developed their practices in self-initiated contexts while endeavoring to extend the reach and visibility of their work to broader publics. Even as progressive art discourse celebrated an emergent multicultural outlook in the late 1980s, narratives around Native American art, culture, and experience remained simplified. Inspired by curator and artist Lloyd Oxendine’s American Art Gallery, founded in SoHo in the early 1970s, institutions such as the American Indian Community House (AICH) and American Indian Artists Inc. (AMERINDA) opened urban spaces for Indigenous representation which thrived outside of conventional value systems. Cultural and operational experimentation abounded and the roles of artist, curator, historian and activist were regularly blurred: G. Peter Jemison, whose early paintings were exhibited by Oxendine, served as the first gallery director of the AICH, while Jolene Rickard, whose photographs complicate separations between Native and American iconographies, is an acclaimed curator and a leading scholar in Indigenous visual history.

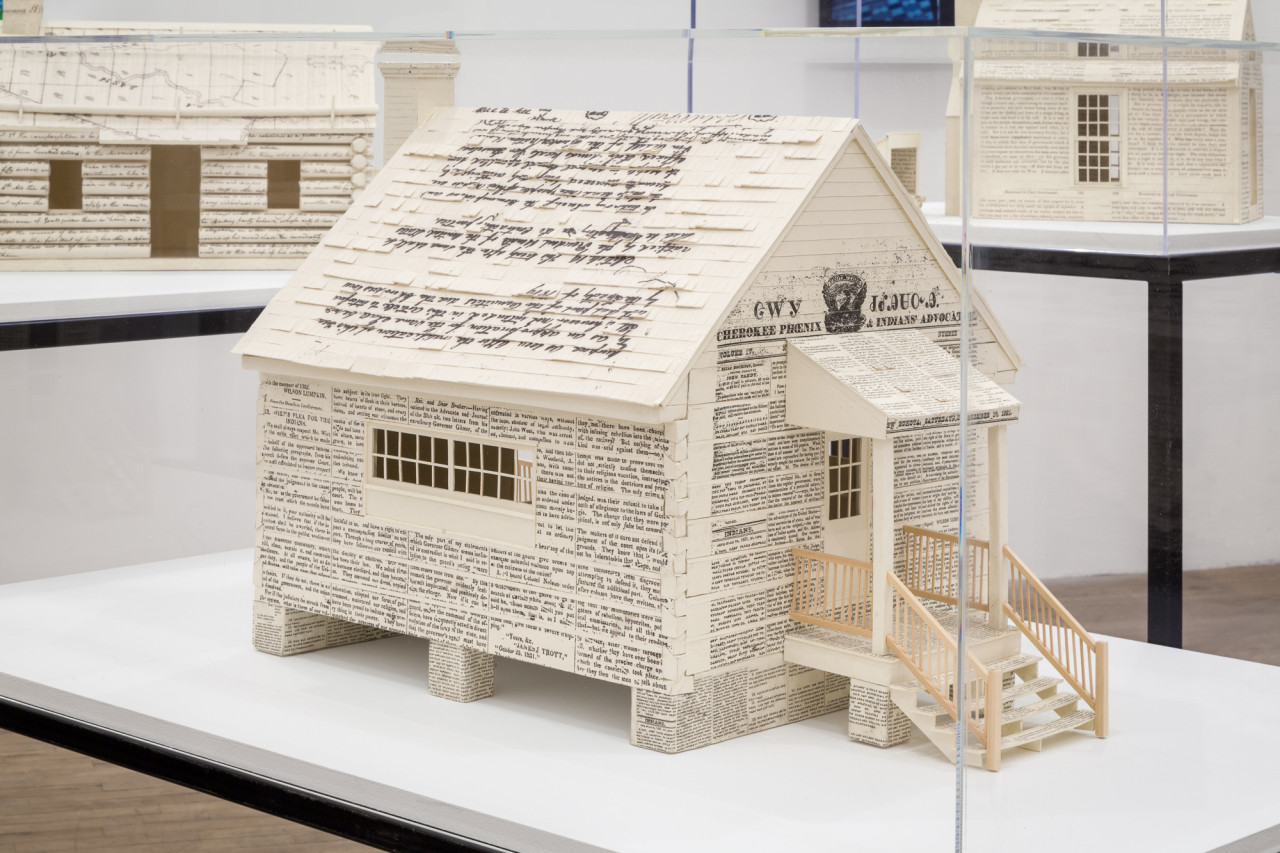

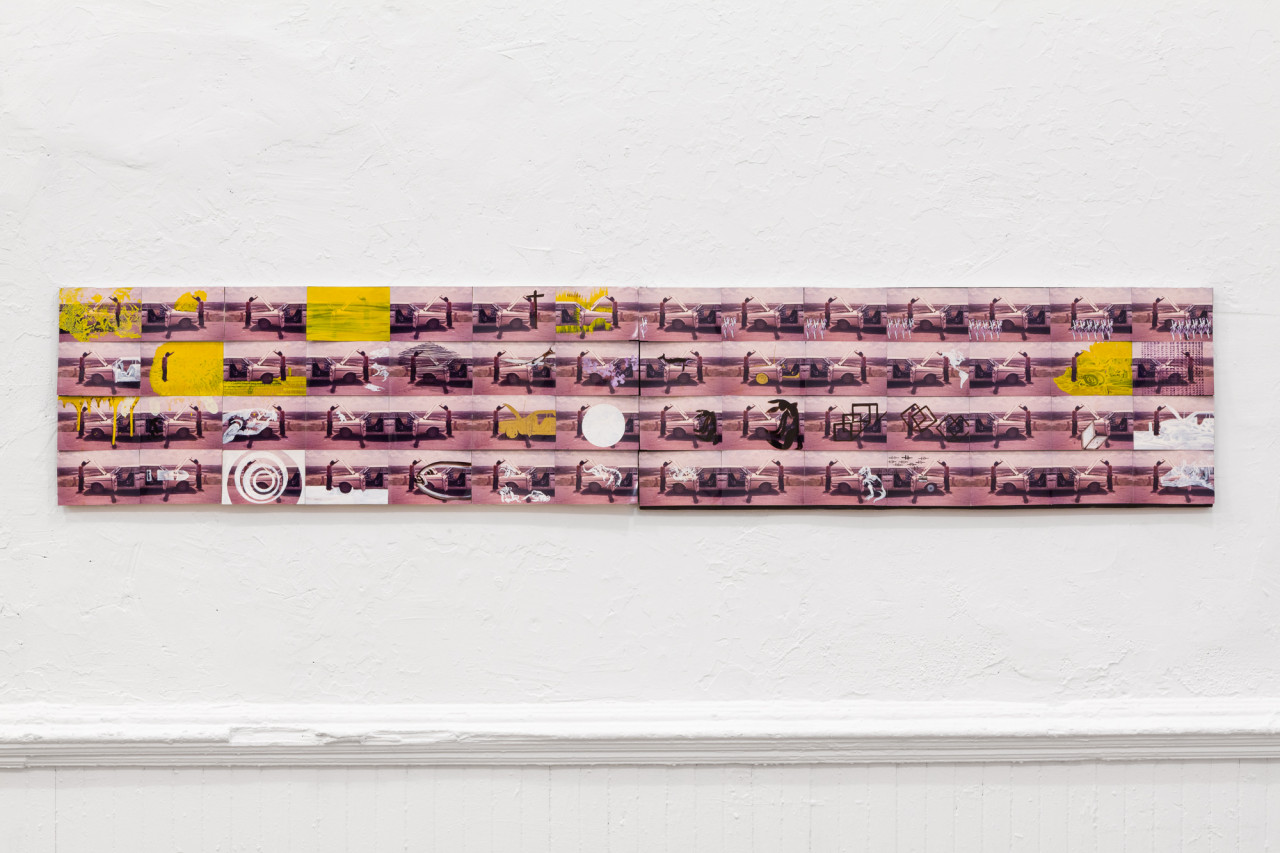

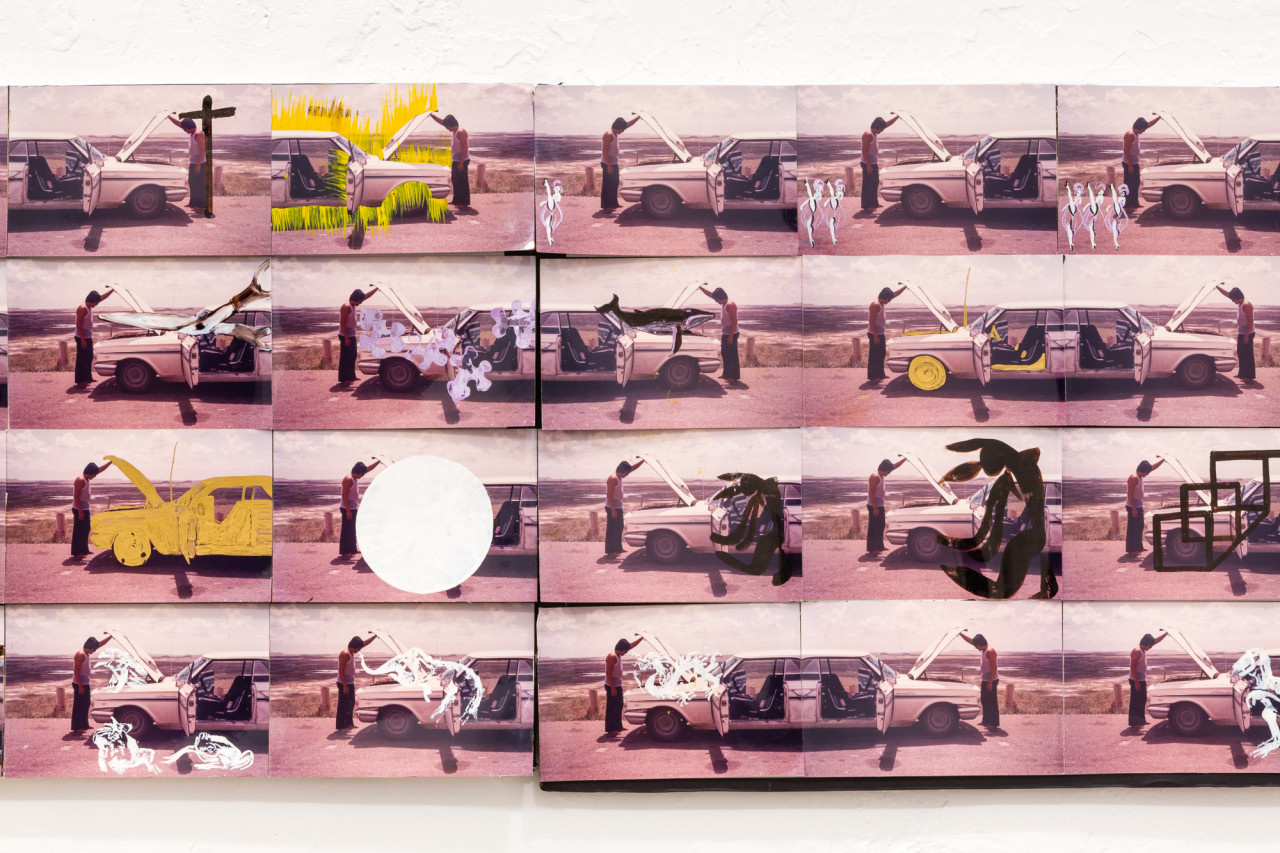

Two exhibitions organized by Jean Fisher and Jimmie Durham in the 1980s notably brought this work into dialogue with institutional and academic contexts: Ni’Go Tlunh A Doh Ka (We Are Always Turning Around on Purpose) at SUNY Old Westbury’s Amelie A. Wallace Gallery in 1986, and We the People at Artists Space in 1987. These exhibitions presented a generation of artists to a wide audience and scrutinized the hegemonic white American gaze by addressing questions of inclusion, framing, containment, and viewership. Artworks such as Pena Bonita’s photomontage series of a car stalled on a reservation road pierced the buoyant postmodern image with a wry political realism. Kay WalkingStick initiated the powerful double visions of her diptychs to complicate how iconography and materiality commingle in landscape painting. Curator and writer Candice Hopkins has noted that, “foregrounding Native artists’ voices rescued their aesthetic legacy from the clutches of modernism, rife as it was with misinterpretation, unequal power relations, and exoticism, and firmly positioned them within the contemporary.” So too, these artists questioned some of the implicit settler colonial assumptions in the contemporary, such as in Alan Michelson's interrogations of linear temporality and the naturalization of economic growth, and carved critical spaces of aesthetic sovereignty.