August 10 – August 20

Born on the La Jolla Reservation in 1950 to a Luiseño Indian mother and a Mexican father, James Luna was an American performance artist, photographer, and multimedia installation artist whose work parodizes western idealized notions of the Indian. Embodying iconic scenes and figures, and altering mass-produced objects, Luna theatrically addresses notions of authenticity, history, memory, and the reverberating impact of colonialism on Indigenous life.

As part of Attention Line, Artists Space presents a selection of rarely or never-before-screened videos, as well as documentation of landmark performances from throughout Luna’s career.

The following films will play during open hours on a continuous loop:

Drinking Piece, 1986

Video, color, sound

18:24 minutes

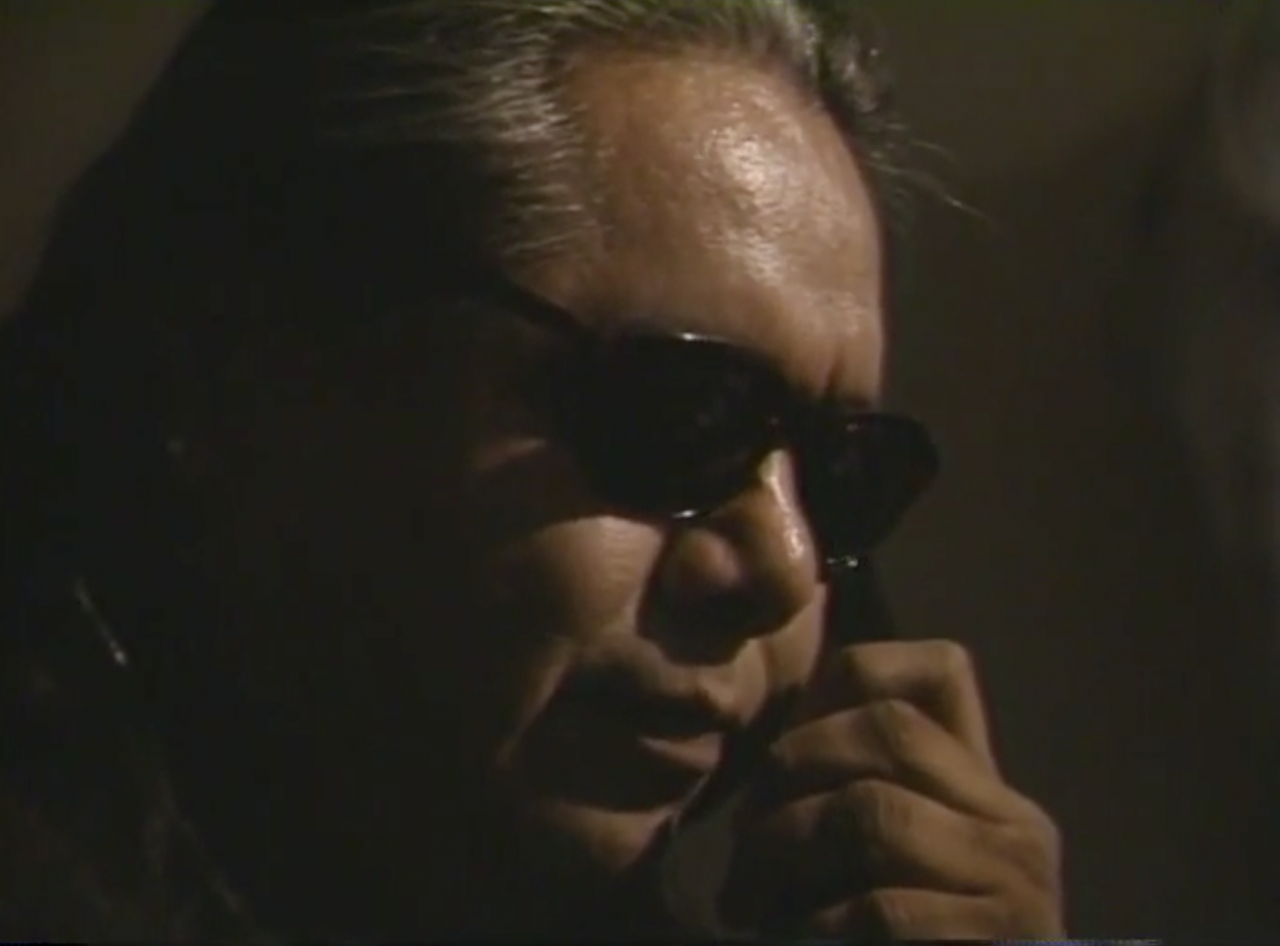

Downing a six-pack of beer in roughly 18 minutes, Luna’s Drinking Piece engages the problem of alcoholism among Native Americans, a theme that recurs in various ways throughout most of his work. The video takes place in a dark room, where a barely visible Luna sits silently drinking and smoking until he finishes the entire pack, upon which he puts on his cowboy hat and exits the frame.

Artifact Piece, 1987/1990

Video, color, sound

8:08 minutes

Artifact Piece documents Luna’s seminal 1987 performance, which was first presented at the San Diego Museum of Man and later at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1990 as part of the landmark Decade Show. The work comprises two vitrines, one with text panels perched on a bed of sand where Luna originally lay for short intervals wearing a breechcloth, and the other filled with some of Luna’s personal effects, including his college diploma, favorite music, and family photos. In the performance, Luna transforms his body into a lighted specimen in order to question the fetishization, museological display, and commodification of Native Americans.

A. A. Meeting/Art History, 1990

Video, color, sound

28:36 minutes

This video begins at an A. A. meeting where four individuals share their ongoing struggles with alcohol dependency and then transitions into a lengthy monologue by Luna, wherein he discusses his relationship to both alcohol and art while drinking two 40 oz. beers. Again, Luna tragically and comically engages the problem of alcoholism in his community while confronting the depiction and treatment of Native Americans within museum contexts and throughout Art History, mediated by his own experience as an Indigenous artist.

Take a Picture with a Real Indian, 1991/2001/2010

Video, color, sound

12:50 minutes

This video documents Luna's performance Take a Picture with a Real Indian, which was first presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1991 and later reprised in 2001 in Salina, Kansas (the version seen here), and then once again in 2010 outside Washington, DC’s Union Station. It is Luna’s most interactive work, as individuals posed with either Luna himself or with three life-size cutouts of the artist (two wearing varieties of traditional Native dress and the third in chinos and a polo shirt). When someone interacted with the work, two Polaroid photographs were taken: one for the participant to take home and another that remained with the work as a record of the performance, which functioned as a kind of tourist attraction.

History of the Luiseño People, 1993

Video, color, sound

29 minutes

Based on his ever-changing performance Indian Tails, this video features Luna sitting alone drinking in a darkened room in front of a TV on Christmas Eve. He calls friends, family, and ex-lovers, excusing himself from all their celebrations. About this video, Luna says, "In the work there is a thin line between what is fictional and what is non-fiction, and what is real emotion and what is art… There is a cultural element where I let, or seem to let, people in on American Indian cultures. There are also elements in the work about American culture that everyone can identify with, and that makes for an understanding that we are all more alike than different.”

Petroglyphs in Motion, 2000

Video, color, sound

36:22 minutes

In his performance Petroglyphs in Motion at SITE Santa Fe, Luna creates a faux-runway environment where he models a series of outfits and characters that mockingly embody different western stereotypes of Native Americans. The concept behind the performance inspired his later 2002 photographic series of the same name, which consists of eight conceptual self-portraits that feature compositions and poses based on ancient petroglyph drawings.

All Indian All the Time, 2006

Video, color, sound

4:45 minutes

In All Indian All the Time, Luna blends his own music with that of rock-and-roll icons such as Jimi Hendrix and Bruce Springsteen, singing, “Now it’s time to let things out… we got it all right here.” The video was made shortly after his 2005 exhibition of the same name, which included many works where Luna superimposed his own image onto publicity photographs of Springsteen and Hendrix, merging his identity with these cultural icons and forcing his audience to question habituated attitudes towards Native culture.

We Become Them, 2011

Video, color, sound

5:07 minutes

In We Become Them, Luna displays a series of slides that feature masks from different Indigenous cultures. As each slide appears on the screen, Luna captures the essence of that mask in his facial expression and demeanor. Luna writes of the performance, “It came to me several years ago, when I was given a mask as a gift. These masks are not costumes, and we are not acting. We do become them. And that’s what I do as an artist.”