June 8 – August 17, 2014

Artists Space

Living with Pop.

A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism

The term “Capitalist Realism” was coined some fifty years ago by German artists Manfred Kuttner, Konrad Lueg, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter when organizing an exhibition of their work in a vacated butcher’s shop in Düsseldorf. Later in 1963, the now legendary “happening” Living with Pop – A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism was staged at the furniture store Möbelhaus Berges.

Living with Pop. A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism is the first exhibition in the US to take an in-depth look at the phenomenon of Capitalist Realism, which for a short period was synonymous with a specific style of post-war West German art. The exhibition aims to articulate this term’s relevance to the social and cultural developments of the past fifty years, leading to its re-appearance in recent political and critical theory.

Living with Pop. A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism documents the actions by Kuttner, Lueg, Polke and Richter that took place between 1963 and 1966 under the auspices of Capitalist Realism, and concludes with an account of the term’s strategic use by gallerist René Block in the late 1960s in Berlin. Further, sections of this exhibition are dedicated to the influence of Fluxus in the Rhineland as an important precursor to Capitalist Realism.

The peripatetic exhibitions that characterized Capitalist Realism as a parodic movement adopted a scenography of furnishings and paintings that constituted a distinct pictorial world. Alongside documentary material, Living with Pop. A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism will also include a selection of over fifty photographic reproductions of works by Kuttner, Lueg, Polke and Richter – a gesture that echoes the artists’ own approach to production and their choice of imagery. The artists painted objects, products and people found in magazines and newspapers, and highlighted the nature of these source materials through the use of fragmented images and other media-based techniques. Mirroring American Pop Art they rejected abstract, metaphorical forms of expression, instead turning their attention to life’s trivialities; By depicting middle-class values, and the repressive mechanisms of Germany’s post-war era, the artists turned the spotlight onto the “Economic Miracle” with its questionable promise of a better way of life.

Living with Pop. A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism also includes contributions by the Düsseldorf/Los Angeles based artist Christopher Williams, professor at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. Williams’ work can be seen to continue the politicized, contextual address of image production synonymous with Capitalist Realism. For the exhibition at Artists Space Williams inserts a selection of films, providing a discursive framework for the historical presentation.

This exhibition is designed in collaboration with Kuehn Malvezzi, Berlin. It is accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue edited by Elodie Evers, Magdalena Holzhey and Gregor Jansen, and published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. The publication includes texts by Darsie Alexander, Eckhart J. Gillen, Mark Godfrey, Walter Grasskamp, Susanne Küper, Susanne Rennert, Dietmar Rübel, Stephan Strsembski, Elodie Evers, Magdalena Holzhey and Gregor Jansen

Artists Space Books & Talks

55 Walker Street

“Konrad was the most informed. After all, we other three had come from the East. He was always lugging around art magazines, and he always had the latest copy of Art International. Konrad knew everyone in Düsseldorf: Alfred Schmela, Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, Manfred de la Motte, Peter Brüning.”

–Gerhard Richter

In the late 1950s, Düsseldorf and the area of Western Germany known as the Rhineland developed into a focal point for a variety of artistic approaches, with international and regional art historical influences beginning to merge in an unprecedented fashion. The chronology of Capitalist Realism, and the practices of Manfred Kuttner, Konrad Lueg, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, can be seen in a new light when this context is considered.

With the founding of the new German State of North Rhine Westphalia in 1949, Düsseldorf became the region’s political and economic centre. The city’s tradition-steeped Art Academy was the first German art college to resume its activities after the end of the Second World War. Two important exponents of Art Informel belonged to its faculty: Karl Otto Götz – who was appointed to a professorship in 1959 and whose students included Kuttner, Lueg, Polke and Richter – and Gerhard Hoehme, a founding member of the Düsseldorf artist group Gruppe 53, who came to the academy in 1960 and to whose class Polke transferred in 1963. Another teacher at the academy during this time was Joseph Beuys, who became a professor in 1961.

Alongside the artists of Gruppe 53 and the later ZERO group, Düsseldorf was also home to the gallerists Jean-Pierre Wilhelm and Manfred de la Motte (whose Galerie 22 existed from 1957-1960) and Alfred Schmela (whose Galerie Schmela was also founded in 1957), who – like Rolf Jährling in Wuppertal and Mary Bauermeister and Haro Lauhus in Cologne – were crucial supporters of new art in the Rhineland.

Wilhelm had particularly close collegial ties with both Jährling and Schmela. Wilhelm and Schmela worked in parallel in Düsseldorf for some time, and their choices of artists were partly complementary. Both of them discovered and supported two of the most important artists of the twentieth century: Nam June Paik and Joseph Beuys, who became closely connected during the Fluxus era.

Yves Klein’s legendary Propositions monochromes exhibition, with which Alfred Schmela opened his gallery on May 31, 1957, was the most striking symbol of Düsseldorf’s birth as a center for the avant-garde. But Jean-Pierre Wilhelm proved to be a key pioneer with his focus on the field of intermedia: this agenda manifested itself most clearly in Galerie 22’s experimental programs, that – after having presented prominent positions of German and French Informel painting – encompassed the premieres of John Cage’s Music Walk, Hans G Helm’s Fa:m´Ahniesgwow and Nam June Paik’s Hommage à John Cage. The gallery’s last exhibition showed works by Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. Sigmar Polke, who had already seen the Bram Bogart and Jean Fautrier exhibitions at Galerie 22, was among the visitors to this final show, as was Konrad Lueg. The paintings Lueg presented in May 1963 in the Kaiserstraße storefront were clearly influenced by Rauschenberg’s blurrings and Twombly’s graffiti-like drawing style.

SR

Artists Space Books & Talks

55 Walker Street

“The first time I painted from a photograph, I did so in a mixture of exhilaration and fear, partly because I was strongly affected by contemporary Fluxus events, and partly also because I once did a lot of photography myself and worked for a photographer for eighteen months: masses of photographs that passed through the bath of developer every day may have created a lasting trauma. There must be other reasons. I can’t tell exactly.”

–Gerhard Richter

Even before Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, Konrad Lueg and Manfred Kuttner had seen the much-cited issue of Art International that introduced them to American Pop Art in January 1963, the arrival of Fluxus art in Düsseldorf and the Rhineland in 1962 had brought with it the conceptual, the real, the concrete, the playful and “inartistic.”

Fluxus, an international reservoir of progressive artistic forces coming from music, literature, theater and the visual arts, was an anarchic and explosive charge – a consciousness-expander that liberated art from the weight of history, from restrictions and constrictions, 17 years after the conclusion of the Second World War. The international movement initiated by the Lithuanian-American artist George Maciunas radically altered the traditional stances taken by producer and recipient, to the extent that the focus was no longer placed on a materially exploitable end product.

The label Fluxus appeared for the first time in March 1961 on an invitation card to a concert at the AG Gallery in New York, cited as the title of a magazine project. Between March and July 1961, the gallery led by Maciunas and Almus Salcius featured a comprehensive program of performances, presentations and exhibitions. Participants included Henry Flynt, Toshi Ichiyanagi, Jackson Mac Low, La Monte Young, Richard Maxfield, Walter de Maria and Yoko Ono, among others. In December 1960 La Monte Young and Yoko Ono had already started to organize an important series of musical, literary and film presentations in Ono’s loft on Chambers Street. After Maciunas was forced to close his gallery for financial reasons, he moved to Wiesbaden, Germany in fall 1961 to work as a graphic designer for the US Air Force. In neighboring Darmstadt – a nucleus of the avant-garde due to the International Summer Courses for New Music held there – Emmett Williams was working for the US Army newspaper, The Stars and Stripes.

Though Maciunas first envisaged Fluxus as a magazine or anthology about performance art and intermedia art, it soon constituted a loosely affiliated movement in Germany. The cosmopolitan Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, who fled from the Nazis to Paris in 1933 and returned to his hometown of Düsseldorf in the 1950s, was an appropriate intellectual counterpart to Maciunas and an under-acknowledged key connector during Fluxus’ defining phase (1962-63).

Thanks to Nam June Paik, who debuted as an action artist with his Hommage à John Cage at Galerie 22 in November 1959, and his mentor Wilhelm – who put Paik in touch with Rolf Jährling of Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal – Düsseldorf and the Rhineland became important venues in Maciunas’s action tour throughout Western Europe in 1962. With the Kleines Sommerfest – Après John Cage (Galerie Parnass, 9 June 1962) and Neo-Dada in der Musik (Kammerspiele, Düsseldorf, 16 June 1962) the “united front against the bourgeois art scene” was initiated, bringing together musicians, artists and literary figures under a common label and positioning itself through a philosophy of experience and continual movement.

The legendary Festum Fluxorum Fluxus organized by Maciunas, together with Paik and Joseph Beuys, took place in February 1963 in the auditorium of the Düsseldorf Art Academy. Flyers featuring Maciunas’ manifesto were thrown into the audience at the beginning of the festival: “Purge the world of bourgeois sickness, ‘intellectual’, professional & commercialized culture… PROMOTE A REVOLUTIONARY FLOOD AND TIDE IN ART.” Richter, Polke, Lueg and Kuttner were amongst the spectators. It was only a short while later, after they attended Festum Fluxorum Fluxus – that was announced as Colloquium for the Students of the Academy on a poster designed by Beuys – that the four artists submitted an application to rent the vacant storefront on Kaiserstraße 31A, leaving the protected space of the academy.

George Maciunas returned to New York in 1963. In 1966 he initiated the Fluxhouse Cooperative Building Projects, a non-profit cooperative to finance artist’s lofts in SoHo.

SR

Artists Space Exhibitions

38 Greene Street

3rd Floor

“This exhibition is not a commercial undertaking but purely a demonstration, and no gallery, museum, or public exhibiting body would have been a suitable venue. The major attraction of the exhibition is the subject matter of the works in it. For the first time in Germany, we are showing paintings for which such terms as Pop Art, Junk Culture, Imperialist or Capitalist Realism, New Objectivity, Naturalism, German Pop and the like are appropriate.”

—Manfred Kuttner, Konrad Lueg, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter

After Manfred Kuttner's and Gerhard Richter's first exhibition at Galerie Junge Kunst in Fulda in 1962, which came about at short notice through the recommendation of Franz Erhard Walther, there were no other exhibition possibilities in sight for them or their fellow Academy students Sigmar Polke and Konrad Lueg.

Avoiding gallery spaces that charged high rental fees, and only exhibited established artists, Kuttner, Lueg, Polke and Richter decided to organize an exhibition of their own. From 4 to 18 May 1963, the artists rented a vacant butcher's shop on Kaiserstraße 31A in Düsseldorf and self-assuredly proclaimed the show to be the “first exhibition of ‘German Pop Art.’” Gerhard Richter exhibited his first photographic paintings, and Sigmar Polke presented the object Mass Media alongside paintings based on illustrations from glossy magazines. Konrad Lueg's pictures showed the influence of gestural abstract painting, but he had begun to combine this approach with pictorial quotations derived from the world of advertising. Manfred Kuttner, by contrast, presented objects painted in fluorescent colors alongside his abstract grid pictures, that already clearly differed from the increasingly figurative program of his colleagues.

The term “capitalist realism” was employed for the first time in the press release for the exhibition. The invitation card's typographic design made use of a list of definitions such as “Pop Art? Know-Nothing genre? Junk Culture?” taken from an article published in the US magazine Art International. The four artists acknowledged the influence of American Pop Art, while their primary experience of such work at that time came only through illustrations in art magazines. Equally, the exhibition's demonstrative quality displayed the impact of Fluxus happenings and actions. Kuttner, Lueg, Polke and Richter's adroit public relations work resulted in several reviews; like the comments in the exhibition's guestbook – which were supplemented by the artists themselves, as well as by Joseph Beuys, under the assumed names of other artists or critics – the press responses ranged from praise to incomprehensibility.

EE

Artists Space Exhibitions

38 Greene Street

3rd Floor

“A number of exhibition concepts were rejected, and it was resolved to hold a demonstration as follows:

a) The whole furniture store, exhibited without modification.

b) In the room set aside for the exhibition, a distilled essence of the demonstration. An average living room as a working exhibit, i.e., occupied, decorated with suitable utensils, foods, drinks, books, odds and ends, and both painters. The individual pieces of furniture stand on plinths, like sculptures, and the natural distances between them are increased, to increase their status as exhibits.

c) Programmed sequence of the demonstration for 11 October 1963.”

—Konrad Lueg and Gerhard Richter

On 11 October 1963, Konrad Lueg and Gerhard Richter put on the now legendary action Living with Pop – A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism at the Berges furniture store in Düsseldorf. Under the pretense of a public relations opportunity, and the potential draw of a new class of customers, the artists were able to win over the Berges owners to allow this intervention.

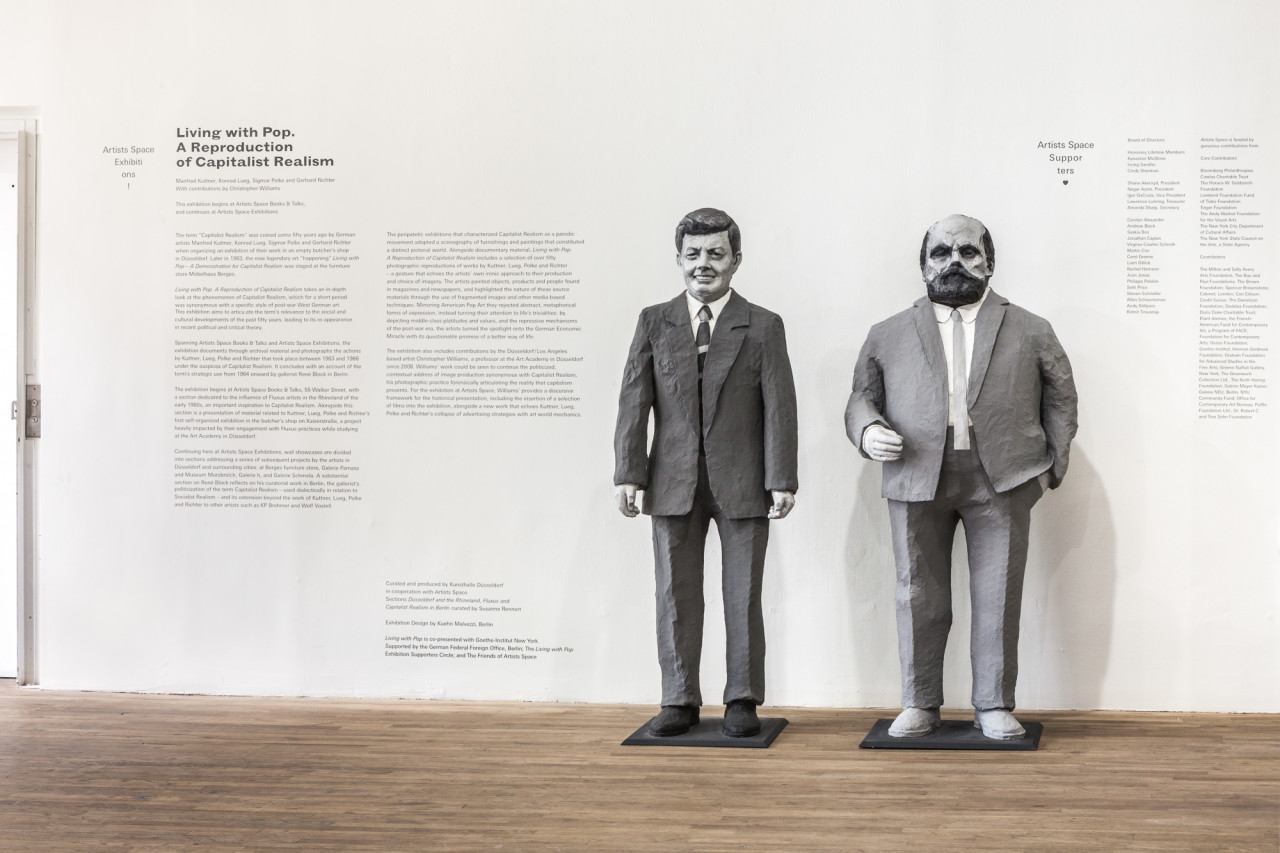

The evening followed a precisely defined choreography. Every visitor was handed a printed program and a number on entering the store, and invited to proceed to a waiting room on the third floor. Here the artists had hung deer antlers belonging to Richter's father-in-law, and placed lifestyle magazines and copies of that day's Frankfurter Allgemeine newspaper. Papier-mâché figures greeted the guests, depicting John F. Kennedy – who had visited Germany several months earlier in June 1963 – and the art dealer Alfred Schmela, who was unable to attend the opening.

A loudspeaker system broadcast music interspersed with the voice of an announcer, who summoned groups of visitors in numerical order from the waiting room, to enter the primary exhibition room. Here, the artists exhibited themselves: they sat in armchairs standing on raised platforms, Richter reading a detective story and Lueg watching a television report on the evening news about the resignation of Konrad Adanauer, the Chancellor of the Federal Republic, who that day had announced his departure from office.

The room had been heavily scented with pine air freshener, and other plinths presented various home furnishings including a tea trolley bearing a vase of flowers, on its lower shelf the written works of Churchill and the home-making magazine Schöner Wohnen. In a wardrobe was placed the “official costume” of Joseph Beuys: a hat, yellow shirt, blue trousers, socks, shoes; to which nine small slips of paper were attached, each marked with a brown cross.

As this room filled with people Lueg and Richter descended from their pedestals and led tours around the rest of the store. Distributed among the furnishings in the other show rooms were a number of recent paintings by the two artists: Four Fingers, Praying Hands, Sausages on a Paper Plate, and Coat-Hangers by Konrad Lueg and Pope, Mouth, Stag and Neuschwanstein Castle by Gerhard Richter. The evening came to a conclusion with several pieces of furniture being damaged and threats by the angered furniture store owner to call the police.

The demonstration, which clearly carried forward the influence of Fluxus happenings, connects central themes of Capitalist Realism. Pop Art's linking of art and everyday life is just as noticeable here as the attempt to criticize the world of middle class consumerism, done so with the help of a trivialized visual language and the ironic treatment of the artist's own works and status as artists. The German “economic miracle” and the constraints of the post-war period similarly influenced the project, that addressed the viewers both as amused spectators and protagonists in their own petty bourgeoisie environment.

EE

Artists Space Exhibitions

38 Greene Street

3rd Floor

“A group of ‘capitalist realism’ artists, Fischer-Lueg, Richter and Polke, telephoned and asked if they could come by sometime and show me their things. ‘Sure,’ I said, ‘with pleasure!’ And indeed the bell rang a while later, and they stood next to a small truck with a tarpaulin in front of the door. ‘Why don't you come outside,’ they said. They had already set up their beautiful large-format paintings in the front garden in the snow. It looked fantastic: Art in snow!”

—Rolf Jährling

On a winter day in early 1964, Kuttner, Lueg, Polke and Richter hired a truck and drove together to Wuppertal and then to Leverkusen. Their first destination was the villa of the art dealer Rolf Jährling, who ran the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, at the time one of Germany's most important galleries for avant-garde art. The action, which became known as the Front Yard Exhibition, constituted a brazen act of self-marketing, as much as a radical break from exhibition conventions. Documented in photographs by Rolf Jährling and Manfred Kuttner, the artists arranged their works packed tightly next to each other on the lawn, flower beds and paths in the villa's snow-covered garden.

Their spectacular performance made a lasting impact on Rolf Jährling, who programmed an exhibition later that year with Lueg, Polke and Richter titled New Realists. Kuttner however was not included in this show, and the episode marked a break in his involvement with the group, his paintings being considered to no longer fit with the figurative stance of Capitalist Realism. On the same day of the Jährling villa “happening,” the artists had traveled to Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen and created a solo presentation of Kuttner's paintings in the garden. Director of the museum Udo Kultermann saw the paintings, but decided against a formal exhibition of the work.

MH

Artists Space Exhibitions

38 Greene Street

3rd Floor

“The painting was almost finished. The Epsal looked at the model, an archive photograph of the meeting of Perry Rhodan and Kroa-Mhakuy on planet Quinta. He compared it to the painting and said, as though to himself: ‘...it's just as well you're conventional, Gucky, and don't mind painting beautiful pictures! You are as close to Rafael as to the Surrealists, the Impressionists, cave-painters, Zero, Picasso, Fluxism and the millions of poor devils who take snapshots of their families. That's your greatness...’”

—Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter

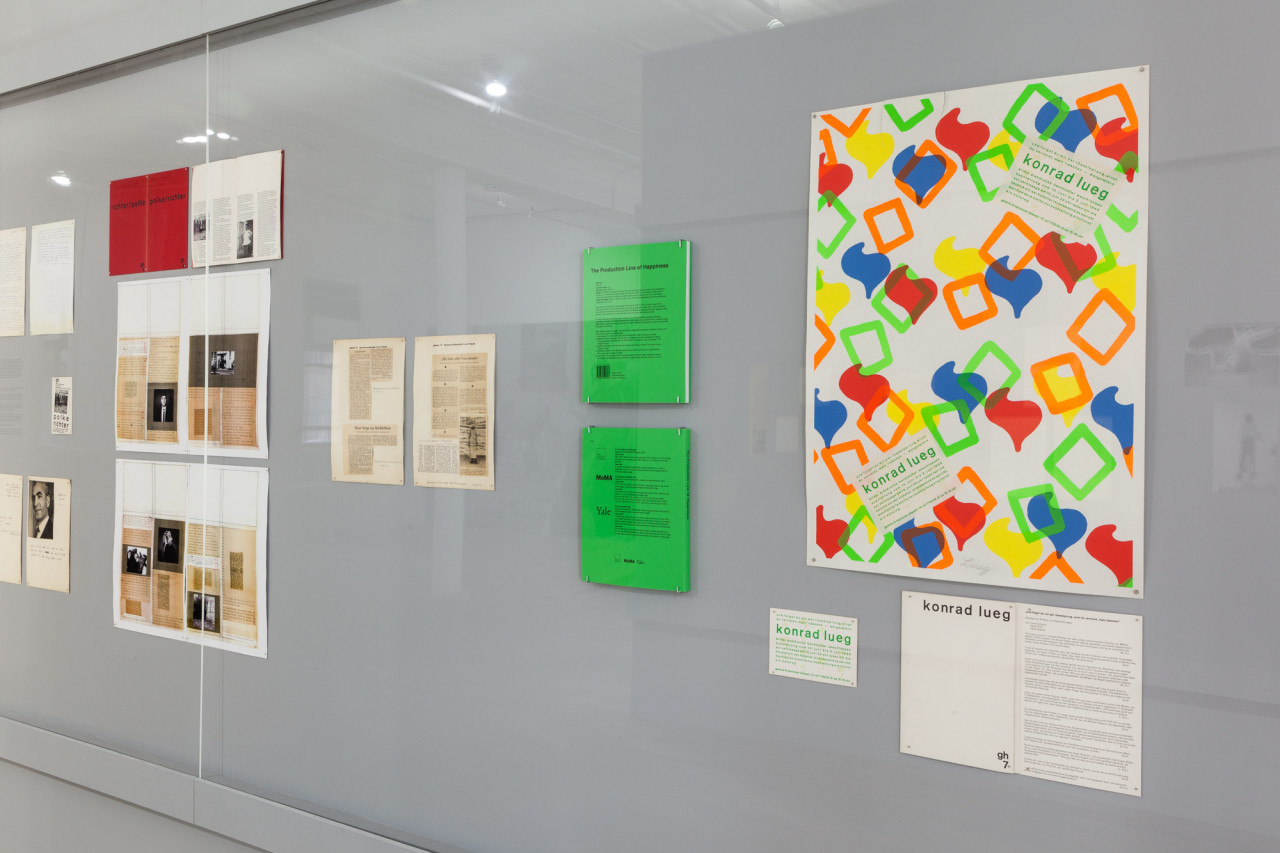

In March 1966, Polke and Richter exhibited together under the title “Pop? Capitalist Realism?” at the Galerie h in Hannover. The exhibition was followed by a solo exhibition by Konrad Lueg in June the same year. The founder of Galerie h, August Haseke, had himself studied at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf and was friends with Lueg, who'd introduced him to Polke and Richter. Haseke had moved to Hannover to work as an art teacher, and ran the gallery in parallel from 1965 to 1970.

Haseke's father-in-law was a printer, and while the gallery ran on basic and largely non-commerical means, this enabled each artist exhibiting with him to produce a catalogue. The joint exhibition of Polke and Richter is of particular significance because it gave them the opportunity to realize an artist’s book that they had planned for a long while. polke / richter – richter / polke combines statements by the artists in cut-up technique, quotations from the popular German science fiction series Perry Rhodan, in addition to photographic material that ironically reflects the petty bourgeois idyll during the years of Germany’s post-war economic miracle, through images of the artists themselves and their families. Haseke went on to publish several important editions by Lueg, Polke and Richter amongst others. Handwritten notes by Richter in August Haseke's archive, containing precise instructions for the position and degree of blurriness that should be applied to his images, documents his meticulousness in the production of such editions.

EE

Artists Space Exhibitions

38 Greene Street

3rd Floor

“We knew [Volker Bradke's] parents well. They really were prototypically middle-class. Unbelievably nice people, but also unbearable. This fascinated... Gerhard, the banality of their lives and the absolute artifice of their apartment décor. [Bradke] was a cliché between bourgeois banality – this way of doing everything precisely and meticulously – and a burgeoning radicality.”

—Gunther Uecker

In December 1966, Richter, Polke and Lueg presented work alongside each other once again for an event that veered between happening and exhibition, and can be seen as the conclusion of their joint endeavors as “capitalist realists” in Düsseldorf. The week-long Homage to Schmela at Galerie Schmela commemorated the departure of the gallery from its original location on Hunsrückenstraße and honored Alfred Schmela, with whom they were all closely tied.

Documented in photographs by Reiner Ruthenbeck, each day between December 9 and 15 a different artist would stage a form of send-off – aside from Richter, Polke and Lueg the project also included Joseph Beuys, Otto Piene, John Latham and Heinz Mack. Sigmar Polke exhibited an installation in which the “higher beings” that ostensibly formed the authority over artistic inspiration made their first appearance in his work. Gerhard Richter escalated his involvement with petty bourgeois reality by exhibiting works centered on Volker Bradke, a young character from the local art scene who was more of an acolyte than an artist himself – the display included a painted portrait of Bradke, a large flag bearing his face at the gallery entrance, film and photographs. Finally, in the artistic demonstration entitled Coffee and Cake, Konrad Lueg turned the gallery space in which the artists' interventions had occurred over previous days into a festive middle-class milieu, replete with patterned wallpaper and dining table serving afternoon tea and cakes. “There are no more aesthetic differences: figure and ground, professor and student, gallery and living room form a continuum in this carnivalesque happening of Capitalist Realism.” (Dietmar Rübel)

MH

Artists Space Exhibitions

38 Greene Street

3rd Floor

“Berlin is an isolated city, unviable of its own accord. It is an ideal city for free creative people who are not dependent on capitalistic or materialistic cravings. It is thus an ideal city for artists.”

—René Block

Having studied applied arts in the Rhineland before moving to Berlin in 1963, gallerist René Block was interested in recent German art made by members of his own generation, as well as in the political and social aspects of the Capitalist Realism label. Its supposed counterpart, Socialist Realism, could be found nearby on the other side of the Berlin Wall, in East Germany and in the Soviet Union.

Block employed the term Capitalist Realism strategically in this specific context during the 1960s and early 1970s – beginning with the group show Neodada, Pop, Decollage, Kapital. Realismus with which the 22-year-old opened his first gallery on 15 September 1964 in Berlin-Schöneberg. Along with Lueg, Kuttner, Polke and Richter, the other participants were KP Brehmer, KH Hödicke, Herbert Kaufmann, Siegmund Lympasik, Lothar Quinte and Wolf Vostell. In subsequent years, Brehmer, Hödicke and Vostell particularly would belong to Block's extended group of Capitalist Realists in Berlin.

While a programmatic emphasis was not yet fully manifest in the title of Block's opening exhibition, despite its clear definition of terms, it would become evident in the following exhibition: Gerd Richter. Capitalist Realism Paintings. Lueg, Richter and Kuttner caught Block's attention for the first time in early 1964 at an exhibition of the Deutscher Künstlerbund in the Haus am Waldsee in Berlin that was headed by Manfred de la Motte. He subsequently got in touch with them in Düsseldorf; Lueg and Richter recommended Polke to him: “Mr Lueg has written to you in the meantime that we are interested in seeing Sigmar Polke be exhibited in your gallery because he is a ‘Pop Artist’ like Lueg and myself. We would be very pleased if that would be possible.” Richter's letter not only reveals enlightening aspects concerning the cooperative or competitive conduct of these four artists at the start of their careers, but it is also interesting to note the emphasis that Richter places on “Pop,” clearly contradicting the attitude taken by Block, whose use of the Capitalist Realism label “was largely in deliberate opposition to American Pop Art.”

The term Capitalist Realism has become fixed in art historical discourse precisely because Block employed it in Berlin with an open-ended, imprecisely defined range of interpretations. These veered between a direct critique of capitalism and affirmative Pop Art. This dialectical method (which is perhaps exemplified by the 1971 publication Grafik des Kapitalischen Realismus which paired images of works by Lueg, Polke and Richter with those of Socialist Realist painters) emphasized the term's contingencies and enabled it to take on a life of its own.

Given this context, Block's wide-ranging initiatives in producing editions should be highlighted as developing parallel to democratizing tendencies in political protest and art of the time. Radical changes in the distribution and economy of art came into effect through the establishment of the first Kölner Kunstmarkt in 1967 by the Association of Progressive German Art Dealers, of which Block was the youngest member.

Between 1974 and 1977 Galerie René Block had a branch in SoHo, New York, at the intersection of West Broadway and Spring Street. The first exhibition held at the space included works by Polke and Richter, along with Joseph Beuys, KP Brehmer, KH Hödicke and Reiner Ruthenbeck. The gallery would later host Joseph Beuys' seminal performance I Like America, and America Likes Me.

Living with Pop. A Reproduction of Capitalist Realism is co-presented by The Goethe-Institut, New York. It is supported by the German Federal Foreign Office.

This exhibition is also supported by the Living with Pop Exhibition Supporters Circle: Marian Goodman, Gordon VeneKlasen, and Thomas Wong & Anne Simone Kleinman, and The Friends of Artists Space.

With additional support from The New York State Council on the Arts, a State Agency.