Dorothy Cochran

In these large woodcuts, which Cochran prints from a huge flatbed press in her basement, elemental forces—storms, whirlwinds, deluges—compete with each other on a near-black surface whipped into movement by the paradoxically precise gouges of a burin. Cochran's exemplars include Blake, Dante, Durer, Ryder; landscape and cataclysm melt into one another in what for her are Biblical epics of creation. For an observer, however, they remain anchored on the page by the crisp, slightly grainy texture of the burch block; by a range of marks, from wispy to thunderous; and by intense, cottony blacks, which Cochran achieves by overprinting and slightly embossing each sheet. The gate to immateriality remains firmly materialized.

Nicholas DeLucia

These photographs at first seem to be creations of the darkrooms, they are composed entirely in the camera's eye, through the the photographer's interest in extreme shifts of scale and perspective. A string high in the branches of a tree, catching the glow of a streetlight, appears to be a UFO streaking in from the stratosphere. Ice melting on a refrigerating coil resembles a giant pear strangely laced with wires. De Lucia insists that the camera's objectivity is itself an apparition believable only as long as the photographer avoids showing us what the lens sees in extremis. In his best pictures the image stubbornly refuses to budge out of the inexplicable, even when its identity is known.

Roger Freeman

Freeman's currency is light. Glowing passages of white—a chef's toque, a set of gates and fences, a strip of beach seen through palms—irradiate the immediate surroundings and cast the rest into darkness. Since a photograph is a record of the passage of light, Freeman's pictures are objectifications of the temporality of his medium; they make light into a "thing" or an "object" intensified into surreality by simple enhancement of sunlight in the series of gates and fences, and in another of billboards, light is squared off in the plane of the photograph. In the beach scenes, luminous swaths of sand hover indeterminately in a space of their own making. Their abstractness is eerily literal.

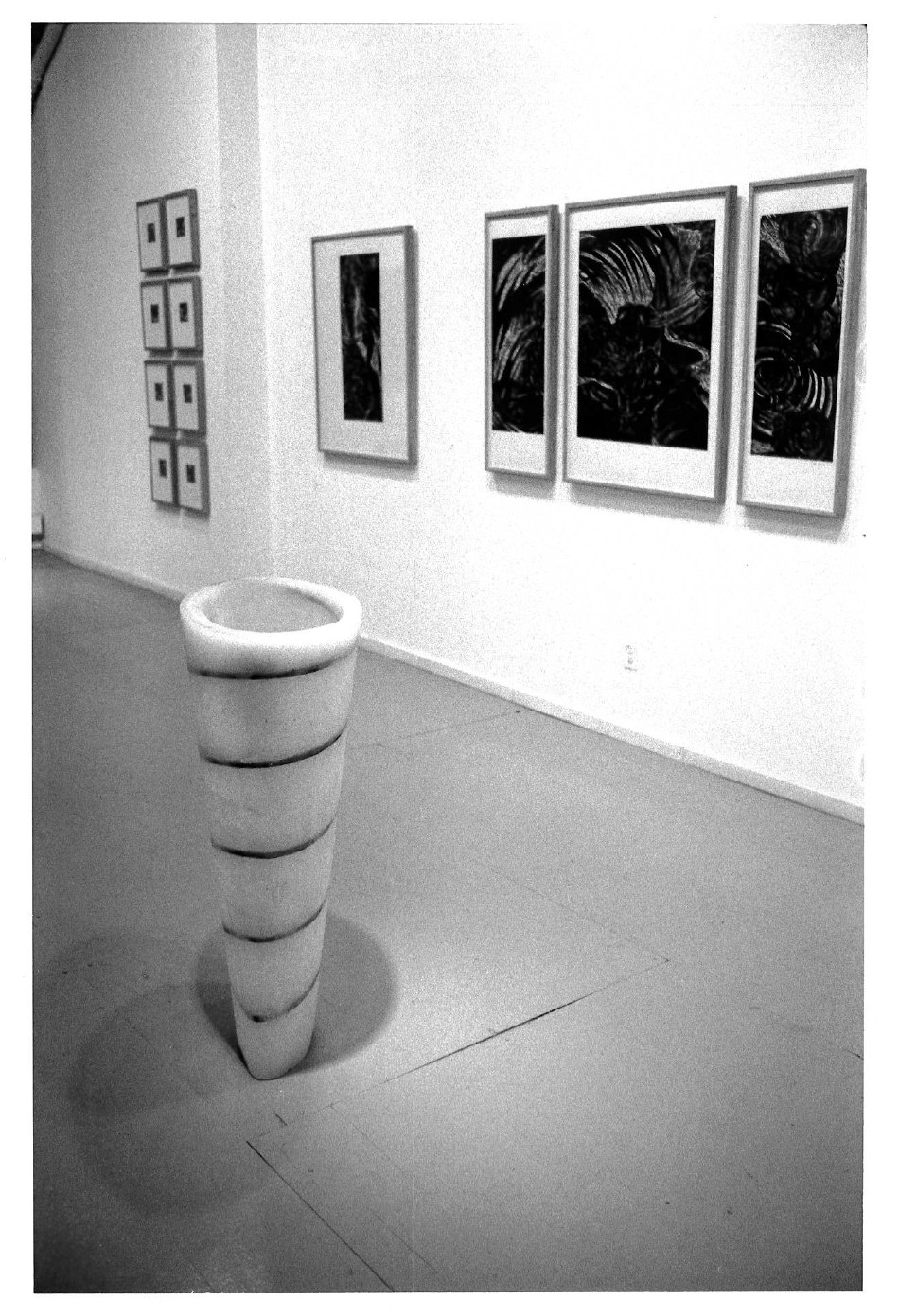

Robin Hill

With steel industrial strapping, or wax and cardboard, Hill "weaves" sculptures whose connecting parts depend for their strength on their ability to bind together. Citing Jackie Winsor as an important influence. Hill professes admiration for work whose shape and substance conform. The tall towers of near-black (or black-ish blue) strapping become a kind of woven three-dimensional drawing. The shorter pillars and tubes are made by stacking circles of cardboard as a core or spine for molten wax; when the wax cools, the materials undergo a phase change into a third, more stable and homogenous state. The gentleness of this sculptural metaphor is enhanced by the wax's pitted, translucent sensuality, which lends these works their persona or sense of presence.

Steven Kasher

In the Biblical Book of Job, Kasher has found a story of suffering, renunciation and triumph that, he feels, has wide application even in an age that resists mysticism. His photographic book uses images to create a separate but interwoven narrative reflecting and commenting on the power of the text. Kasher likes the fact that a few of these pictures are widely known and therefore part of our common experience; others present strictly private associations. Some images are from his own photographs. Others have been borrowed from photographers whom Kasher admires: Richard Avedon, Harry Callahan and Robert Frank. The rest are picked from old books, postcards, or antique prints, such as the picture of the death masks of Delacroix and two other artists, an image which speaks to him of creativity and mortality.

Julian Lethbridge

The spontaneity of Lethbridge's nearly calligraphic black gestures is deceptive. He provides a foundation by first laying down a pattern or template and stenciling in a faint gray set of marks, a "frame" which may be repeated several times within a single picture. The regularity of his paintings and drawings is contradicted by the application of a second layer of pigment, this time pure black and brushed in by hand. One sense that Lethbridge likes the way spontaneous gestures of the hand in Japanese art seem to float on a more studied background.

Thor Rinden

By Laying down a set of rules for the shape of his paintings (repeatable with slight variations) Rinden can concentrate the fine gradations of texture, color and handwork in the paint-surface. Each canvas is actually two: an outer "frame" about six or eight inches wide, and an inner square mounted with just a hairline crack between them. Since the crack can separate the two surfaces without immersing Rinden in the problems of painting a line, each part of the picture can become its own arena for pigment. The pigment itself is richly various: sanded, scuffed, layered, sometimes mixed with wax, sometimes buffed to a soft shine. One is reminded of Josef Alber's color-exercises, in which an economy of means does not produce minimal results.

Jacques Roch

Upset by what he considered the excessive softness and sentimentality of French painting in the 1950's, Roch retaliated by drawing cartoons, whose sharp black-and-white lines appealed to him for their emotional and formal precision. The legacy of that early interest can be seen in his recent paintings. In a red or blue (or, rarely, black) expanse of paint are suspended creatures drawn with a few simple lines. Roch thinks of them as male and female principles. They are transparent, like archetypal beings from myth or nightmare.

Jessica Stockholder

In the assemblage tradition, artists pick up junk and convert it into fine art; Stockholder insists that it retain its character as junk. She speaks of stripping art of the aura of preciousness it acquires in museums. Her installations, built up of industrial or cast-off materials (aluminum studs, wire lath, plaster, furniture, wood, sheetrock, and so on), are not elegant or east. Her blue-collar constructivism is a "concrete poetry" of common things.

Peter White

Searching for a way to approach landscape from a contemporary viewpoint, White was struck by the complicated issues of space and light that exist within a grove of trees. His forests are almost violently lush. Their sense of the heroic is assisted by their scape: each canvas is the width and height of White's reach when his hand holds a paint stick. Each seems big enough, in other words, to be walked into, but for the apparent density of timber. White's new work includes the stark trunks of charred birches; burned forests present a different rhythmic pace.

Tad Wiley

From two-inch blocks of yellow pine, Wiley saws and glues angular forms and covers their front sides with a thick skin of marine enamel. They extensively refer to minimalism's well-fought-over skirmish line between painting and sculpture, but their increasing subtlety comes to their assistance. The pine itself is a substantial chunk of matter, too thick to be anything but grossly physical, and its angles are unusual enough to suggest some organic basis for its shape. These faintly humanoid references are insistently denied, however, by the glossy commercial sheen of a polyurethane-based paint.

Philip Zimmerman

These 30 drawings comprise a book of visionary characters based on Zimmerman's observations of the underworld of the mind—themes of obsession, love and death, and the "wedding" of good and evil, beauty and horror. He says that the project came into focus for him when, in a "caffeine den" in Portland, Oregon, he say near a strangely dressed man who announced to his female companion, "Fear not, I am with thee." The Biblical promise of release is just a teaser, however. Zimmerman remains fascinated with Hell. In these felt pen drawings, the naif discovers a gift for nightmare.