August 7 – August 31, 2020

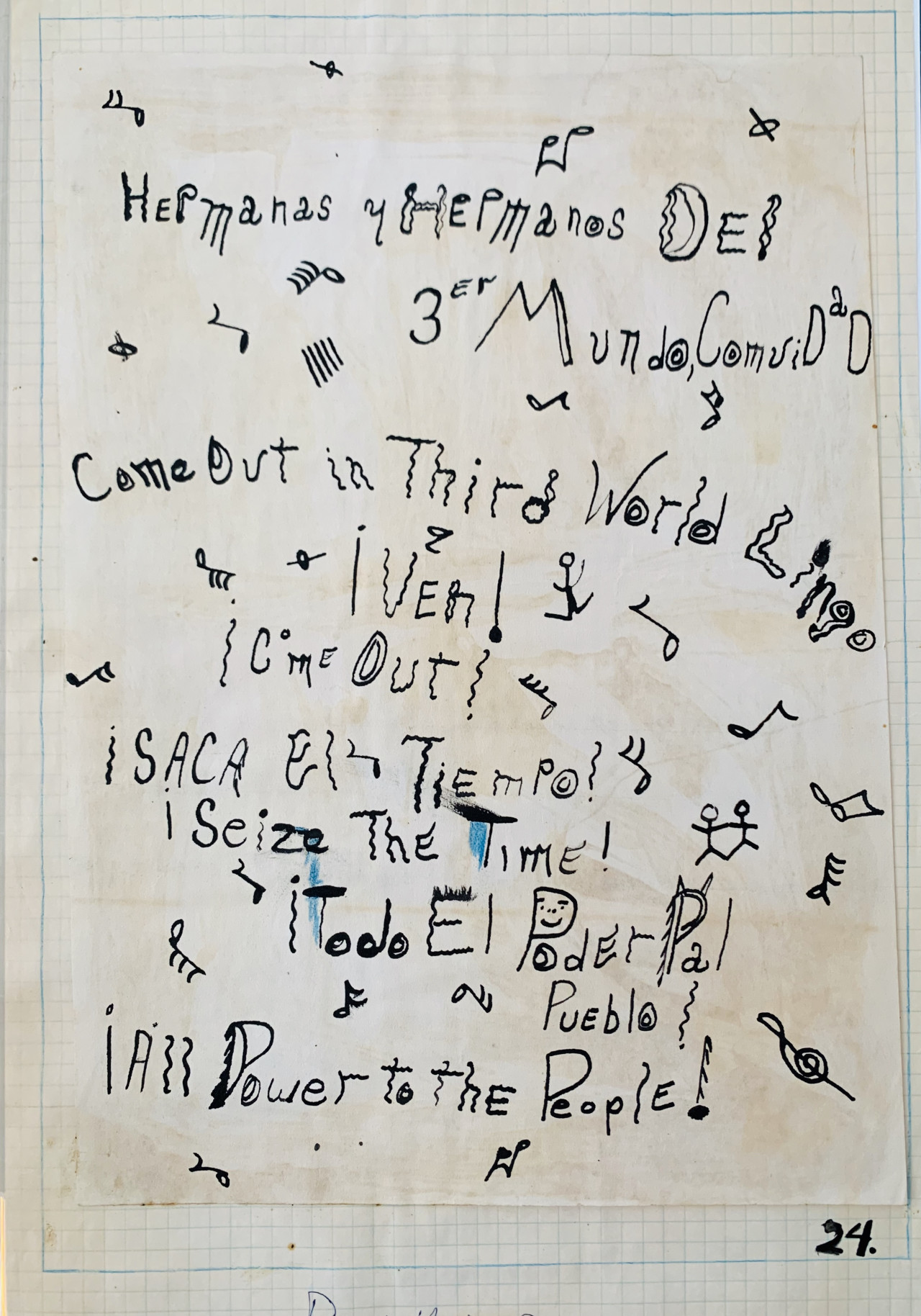

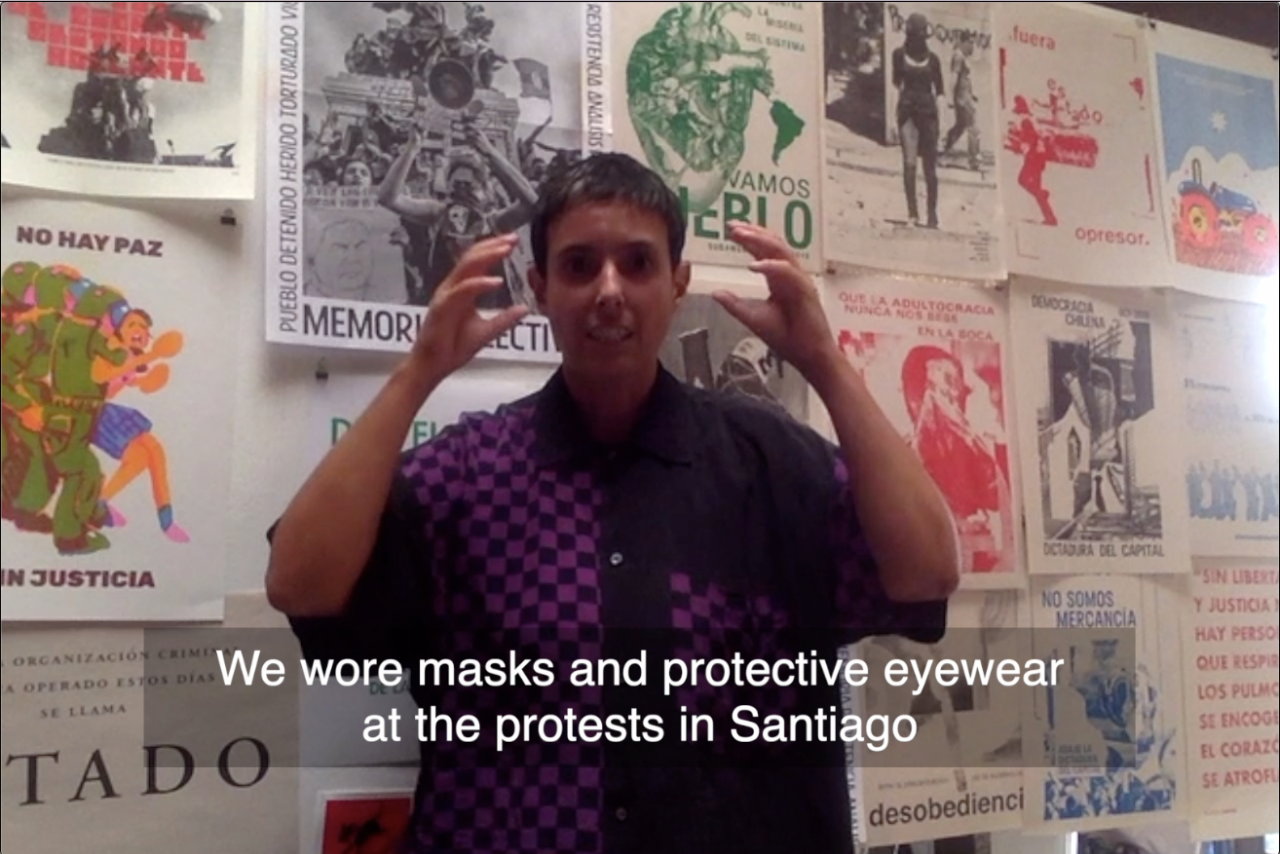

On a sunny, cloudless day in June 1982, five decommissioned World War II planes took off from Flushing Airport in Queens, New York. In white smoke-dots blotted across the sky, they typed out a poem, "La vida nueva", by the artist and poet Raúl Zurita as he and a group of friends and artists looked on. The work referenced the 1973 U.S.-led military coup against the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende and the subsequent dictatorship in Chile. After La vida nueva takes its name from this work of Zurita's and turns back to this era that was full of the promise and violence of the new, to bring us a sense of a moment in time lost and imperfectly recovered. Through video, installation, sculpture, poetry, performance and archival documentation, the works explore constructions of self and nation by sifting through the unstable terrain of the past. Drawing on histories and archives of feminist, queer, and Third World liberation movements and responding to the uneven forces of neoliberalization, the artists suggest the pursuit of a new life that is concomitant with new ways of being together.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, After La vida nueva consists of an expanded catalogue, available for download, and an online component, hosted by Artists Space, where a weekly series of “spotlights” of different works in the exhibition will include screenings, archival documents, images, and text.

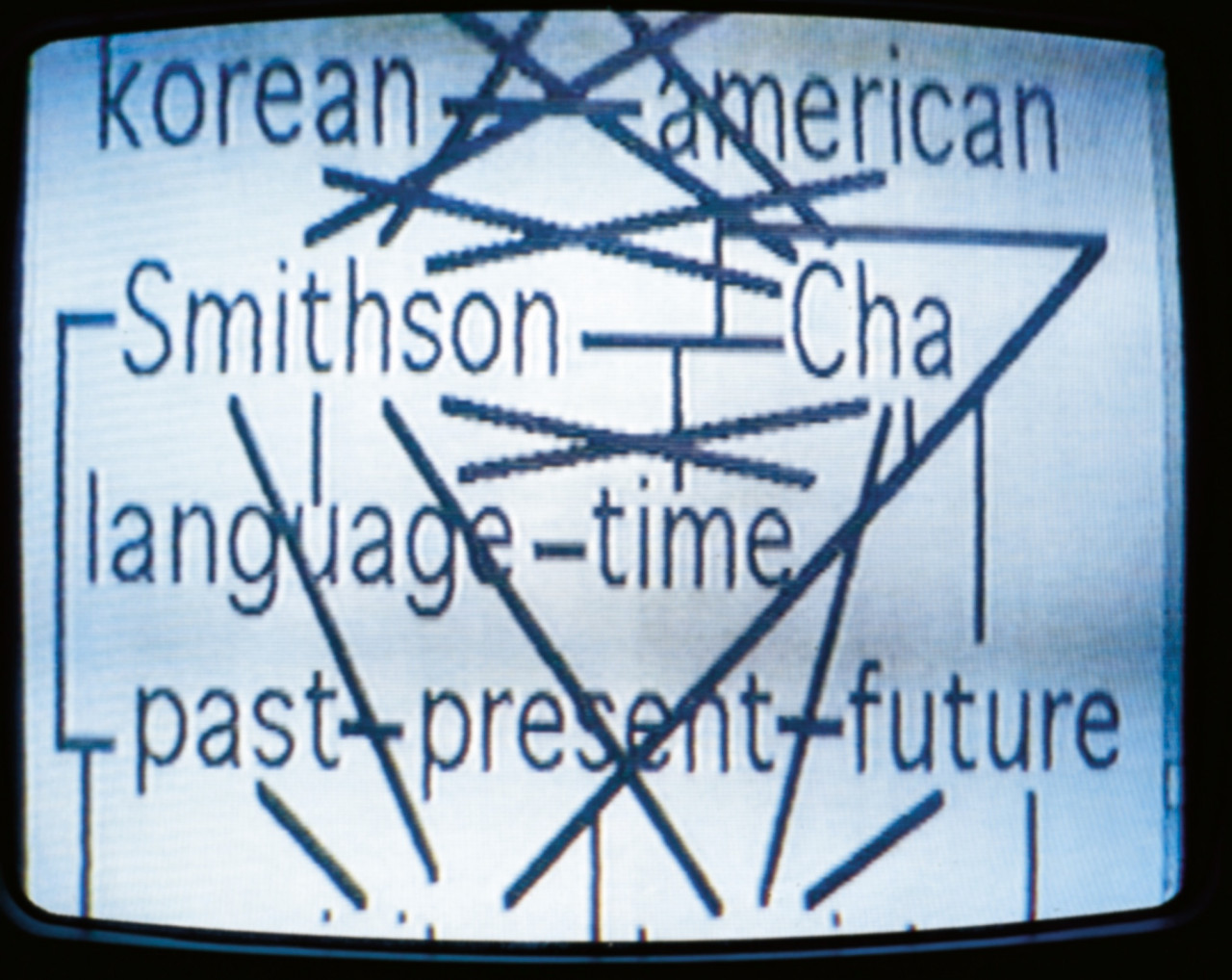

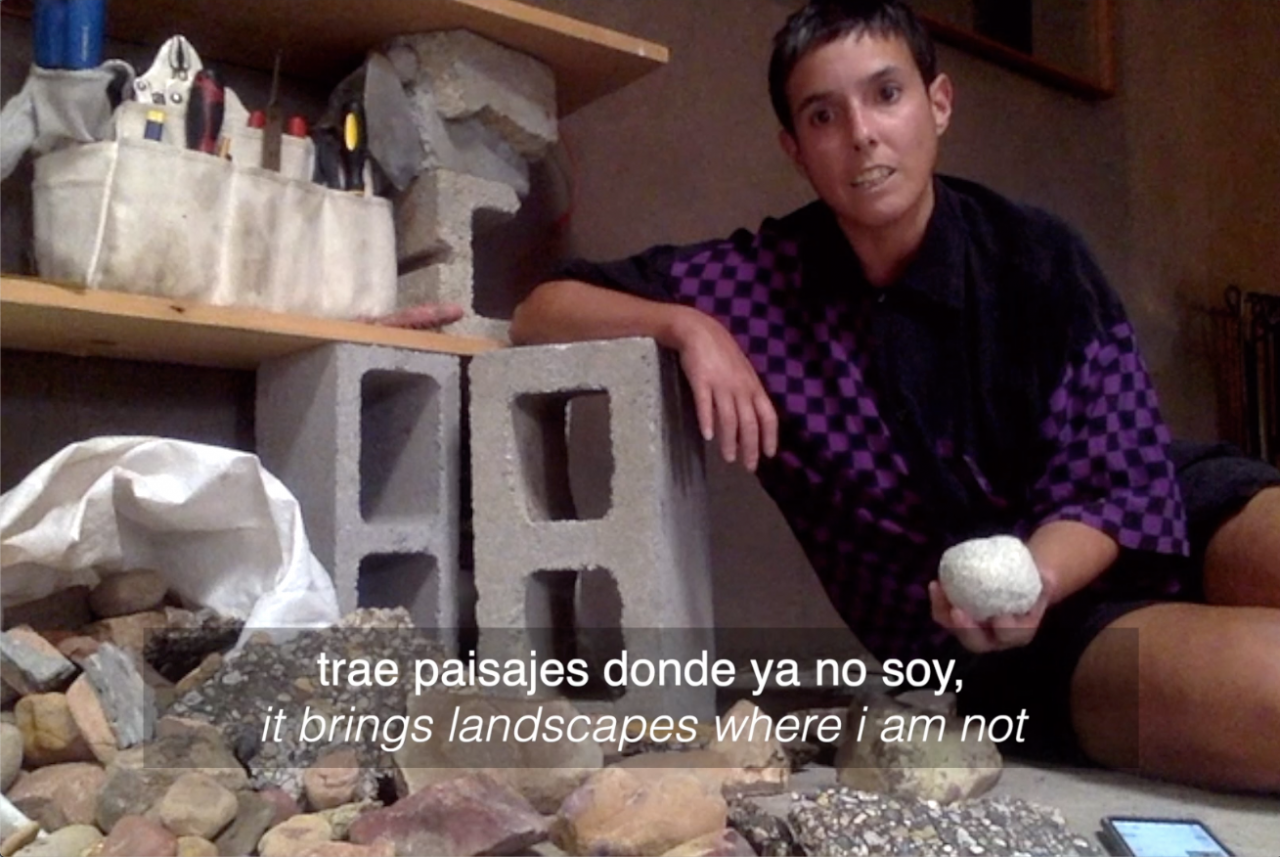

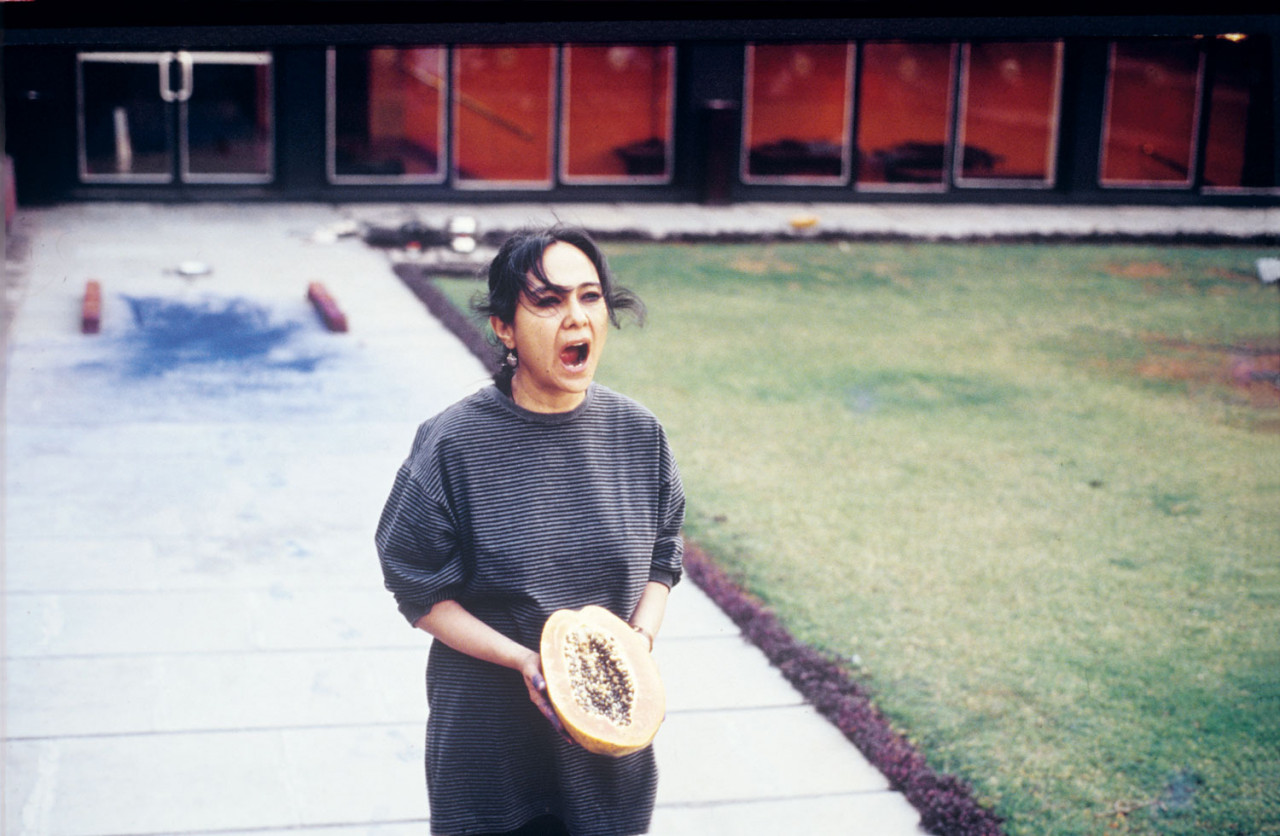

The exhibition features works by Amelia Bande, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab, Renée Green, Rummana Hussain, Caroline Key, Alan Michelson, Rashaad Newsome, Catalina Parra, Cici Wu, and Raúl Zurita.

August 8 – 15: Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Renée Green, Caroline Key, and Cici Wu

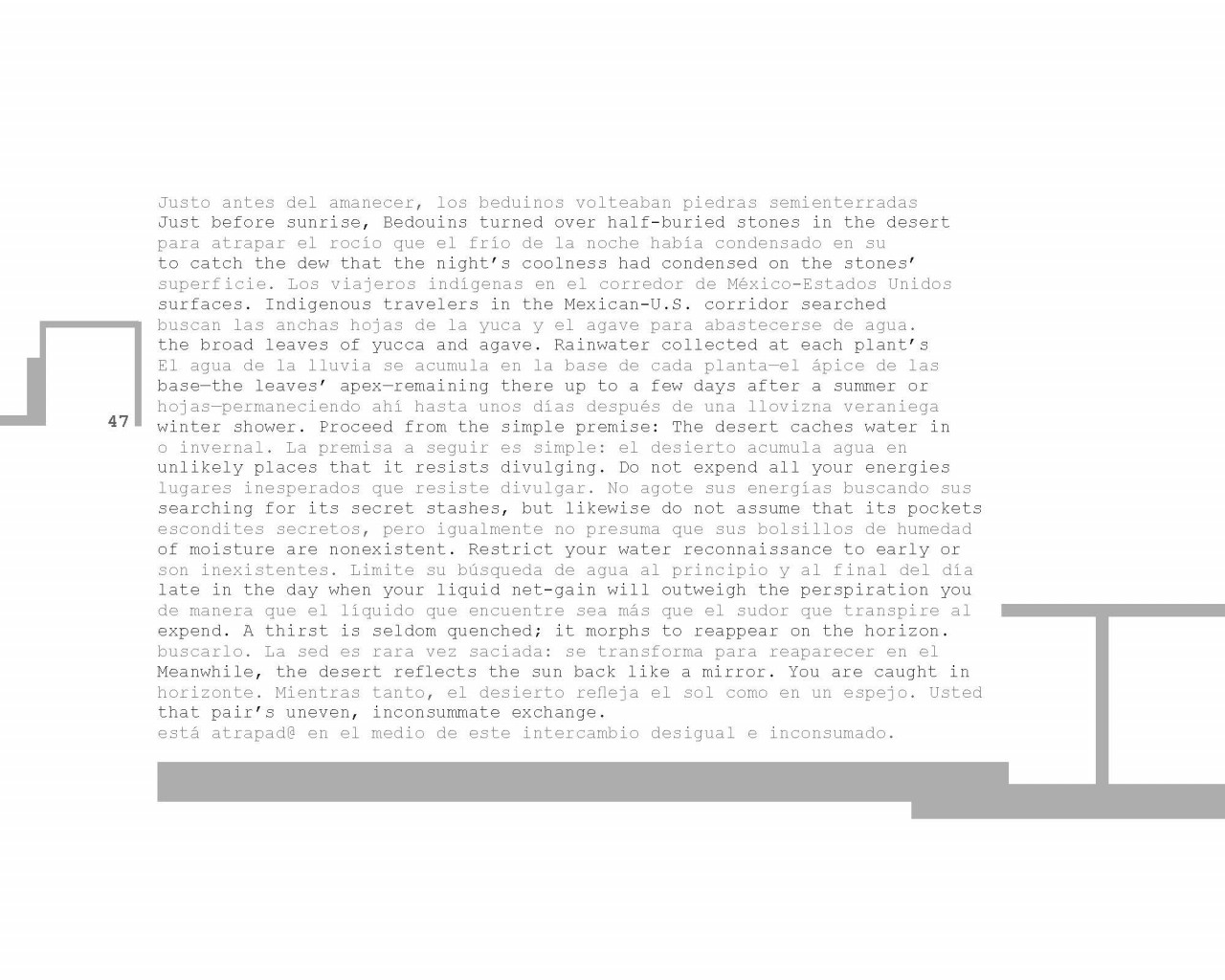

August 16 – 23: Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab, Alan Michelson, Rashaad Newsome, and Catalina Parra

August 24 – 31: Amelia Bande, Rummana Hussain, Third World Gay Revolution and Juan Queiroz, and Raúl Zurita

Curated by Weiyi Chang, Sofia Jamal, Colleen O’Connor, and Patricio Orellana, the 2019–20 Helena Rubinstein Curatorial Fellows of the Whitney Independent Study Program.